Codger_64

Moderator

- Joined

- Oct 8, 2004

- Messages

- 62,324

Kent Knives - F.W. Woolworth

I find that knowing the story behind a knife makes collecting and ownership more enjoyable. Sometimes we luck out and get the personal story of first purchase and ownership from the original buyer, but most often not. Then it takes a bit of sleuthing to get the full story, particularly with privately branded knives (SFO’s or “Special Factory Orders” . Who made the knife and for whom? When did they make it and what were they trying to achieve during the market that prevailed at the time?

. Who made the knife and for whom? When did they make it and what were they trying to achieve during the market that prevailed at the time?

Over the past few years I bought several patterns of these inexpensive folders just to explore the materials and construction. The stamping is currently not very popular among those who know, or don’t know it’s origins, much like the Sears Craftsman knives were a few years ago, so one can often pick these up at very reasonable prices. The marking is KENT - N.Y. CITY - U.S.A.

Now, most of us know that few, if any knives were actually manufactured in New York City, though there did exist a section of one street known as “Cutler’s Row” where many importers, jobbers, and manufacturers had their offices located.

When we look up the mark in Goins Encyclopedia Of Cutlery Markings (1998), we see that he attributes the mark to A. Kastor & Brothers (Camillus) as used on knives manufactured circa 1931-1955 for F. W. Woolworth.

As with Sears Roebuck & Company, F. W. Woolworths was the brainchild of one merchant pioneer who based his store on a successful formula. Frank Winfield Woolworth (1852-1919) was the originator of "five-and-ten-cent" stores.

Frank was a farm boy in upstate New York who began his merchant career as a clerk in a drygoods store in Watertown New York From a website archive:

In 1873, he started working in a drygoods store in Watertown, New York. He worked for free for the first three months, because the owner claimed "why should I pay you for teaching the business". He remained there for 6 years. There he observed a passing fad: Leftover items were priced at five cents and placed on a table. Woolworth liked the idea, so he borrowed $300 to open a store where all items were priced at five cents.

Impressed with the success of a five-cent clearance sale, he conceived the novel idea of establishing a store to sell a variety of items in volume at that price. With $300 in inventory advanced to him by his employer, Woolworth started a small store in Utica in 1879, but it soon failed. By 1881, however, Woolworth had two successful stores operating in Pennsylvania. By adding ten-cent items, he was able to increase his inventory greatly and thereby acquired a unique institutional status most important for the success of his stores.

Woolworth's first five-cent store, established in Utica, New York on February 22, 1879, failed within weeks. At his second store, established in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in April 1879, he expanded the concept to include merchandise priced at ten cents. The second store was successful, and Woolworth and his brother, Charles Sumner Woolworth, opened a large number of five-and-ten-cent stores. His original employer was made a partner.

The growth of Woolworth's chain was rapid. Capital for new stores came partly from the profits of those already in operation and partly from investment by partners whom Woolworth installed as managers of the new units. Initially, many of the partners were Woolworth's relatives and colleagues.

Convinced that the most important factor in ensuring the success of the chain was increasing the variety of goods offered, Woolworth in 1886 moved to Brooklyn, New York, to be near wholesale suppliers. He also undertook the purchasing for the entire chain. A major breakthrough came when he decided to stock candy and was able to bypass wholesalers and deal directly with manufacturers. Aware of the importance of the presentation of goods, Woolworth took the responsibility for planning window and counter displays for the whole chain and devised the familiar red store front which became its institutional hallmark.

The success of the chain between 1890 and 1910 was phenomenal. The company had 631 outlets doing a business of $60,558,000 annually by 1912. In that year Woolworth merged with five of his leading competitors, forming a corporation capitalized at $65 million. The next year, at a cost of $13.5 million, he built the Woolworth Building in downtown New York, the tallest skyscraper in the world at the time. Cass Gilbert was the architect, and it was engineered by Gunvald Aus. Another rare fact about the Woolworth Building -- it served as the company's headquarters right up until Woolworth's 1997 declaration of bankruptcy. By 1997, the original chain he founded had been reduced to 400 stores, and other divisions of the company began to be more profitable than the original chain. The original chain went out of business on July 17th, 1997, as the firm began its transition into Foot Locker, Inc.

The UK stores continued operating (albeit under separate ownership since 1982) after the US operation ceased under the Woolworth name and now trade as Woolworths.

Vital statistics 1929

total annual sales in the US and Canada $272,754,045

11,000 bales of cotton used to weave towels alone, with 2,000 looms working 24 hours a day and employing 1,000 people

over a million mousetraps sold every year

100,000,000 shaves with Woolworths blades during 1929

over 1,000,000 nets and 5,000,000 printed curtains sold

7,500,000 tons of yarn used to make men's socks

90,000,000 lunches served to customers during the year

4,000 miles of pencils if laid end to end and 300 miles of pen points

33,000 miles of garter elastic

1929? Why would I back this up to mention 1929?

Well, many retailers and manufacturers bit the big one in the Great Depression of 1929-1932. The list of cutlerys and hardware jobbers which closed is large.

1929: Remington sold out to the Dupont Company.

1930: Schatt-Morgan Knife Company filed for bankruptcy.

1931: New York Knife Company went out of business, the factory was closed due to bankruptcy.

However, some not only survived but thrived. Woolworth's and A. Kastor & Brothers / Camillus were such companies. Their success was largely due to innovative thinkers able to meet a vastly changed marketing landscape.

Circa 1931-1955...? Oh, how can I tell a story of the American knife industry without mentioning Albert Baer!

Albert M. Baer was put in charge of sales in 1930. Albert signed George Herman ‘Babe’ Ruth to endorse autographed baseball bat figural knife for Kastor Bros., first of many endorsements. In order to permit Baer to be a stockholder, Alfred B. Kastor sold him 50 shares of his common stock

Under Baer's management of sales, Camillus manufactured KENT brand knives for F.W. Woolworth's beginning in 1931.

Excerpts from the A.M.Baer Memoirs:

"My habit was to go to the Woolworth Company every Christmas and every New Year and thank them for the business they gave us. This started in 1923 because I got the inspiration that any company with the number of stores that Woolworth had, should be the outlet for the products that we made at Camillus Cutlery, regardless of the fact they had a limit of 10 cents in the east, and 15 cents in the west.

George's predecessor, Mr. P. G. Franz, lived in Buck Hill, Pennsylvania, and he had an apartment at 86th Street and Central Park West. He traveled to Europe regularly to their main headquarters in Crayfell, Germany and was punctilious about never going to lunch with anybody or not even accepting a book when he sailed on the Europa. P.G. liked me and although I had practically nothing to sell, I still called on him and was particularly fond of his assistant, a woman 10 years my senior, named Mrs. Kissack. Mrs. Kissack always tipped me off when I phoned for an appointment as to whether P.G. was in good mood or not. All the years I called on him, he called me "Mr. Baer" and he was always "Mr. Franz." One day Alfred Kastor showed me a sample of a two-blade metal handle Jackknife that

Mr. Gerling had sent us, and quoted us 3 cents a dozen. Now the tariff on importing knives advanced considerably with knives when sold at over 39 a dozen both ad valorem and specific. If you don't know customs terms, ad valorem is a percentage of the value and specific is a set amount per knife. 3~ knives, FOB Germany, landed in this country at about

57. I never asked Alfred anything but took the samples down to P.G., told him what we paid for them, where we bought them. He knew Gerling and P. G. wrote up a general order to be shipped to all stores for 10,000 gross. Big deal! He paid me 85 a dozen. I brought the order back to the office and I thought Alfred would flip. He practically made a special trip to Germany and placed the order, and we were in business with Woolworth selling them 10 cent pocket knives. They sold like hot cakes and in the midst of the sale, over the Wall Street ticker, came word that Woolworth was about to sell 20 cent merchandise. Here was the opportunity of a lifetime. Now we could make a Camillus product in the USA and boy, we needed the business. I was down to see Franz the same day word came out, and he agreed that we should submit some samples, for he said he wanted to get prices and samples from other factories, particularly a company in Providence called Imperial, for they had been trying to make 10 cent knives in the United States for him and he heard that they gave good value.

I had no sooner returned to my office that I had a phone call from him asking me to come back. When I did, he was shaking with anger. "What do you think?" he said. “The American Cutlery Industry, led by Domenic Fazzano of Imperial have lodged a complaint claiming that the 10 cent knives which you sold me were undervalued, and we have to go to Customs Court to fight the case. How dare they on one hand come to try to sell me, and on the other hand act in this underhanded way?"

I told P.G. not to worry. We had done nothing illegal. We would stand behind him and Woolworth and fight this case. I suggested that he get two samples from Imperial as though nothing had happened, so we would see what they were going to offer competitors. He smiled and said “Wonderful. We’ll, fight fire with fire! “ It was not long before we had the sample roll of the 10 knives Imperial had submitted to the Woolworth Company. I took the knives to the factory. We discussed the quantities involved, took the prices that Imperial had quoted Franz and duplicated the patterns as best as we could, and down I went to see P.G. I got him to pay us a little bit more than

Imperial because we made a better product. He paid us $1.505 a dozen and he sold them for 20 cents each.

When the knives hit the stores, they were a sensation. The sales were enormous. You could go and count how many they sold per hour. In fact, I did just that, and we started to mechanize the Camillus factory as a result of the Woolworth order. P.G. never told Imperial why they lost the business, for certainly had Domenic not been part of the conspiracy to embarrass me, they would have had this business.

The hearing in the Customs Court took place, and we were able to prove that there was no chicanery. The case was dismissed and with tears in his eyes, P.G. Franz looked at me and said “As long as you live, Mr. Baer, we will let you be competitive, and if you meet competition, you will always have our business.” This message he passed on to George Graff and for all the years that I was with Camillus, George lived up to P.G.’s admonition. When George Graff became the buyer of Woolworth, I was selling several knives to him. George seemed like a nice guy. He came out of the Chicago district office. He knew about and liked ..to sell pocket knives...

And in fact, when George Graff did take over as the buyer for Woolworth, he continued buying from Baer. And then in October 1940, Baer left Camillus in a tiff with the Kastor brothers. And most of the buyers, Sears’ Col. Tom Dunlap and Woolworth's George Graff included, followed Albert to his new company, Ulster. Another excerpt:

George Graff, the Wool-worth buyer, wrote a letter to the Board that Camillus was a ship without a rudder. That didn't sit well with Alfred Kastor, for F. W. Woolworth was their #2 client.

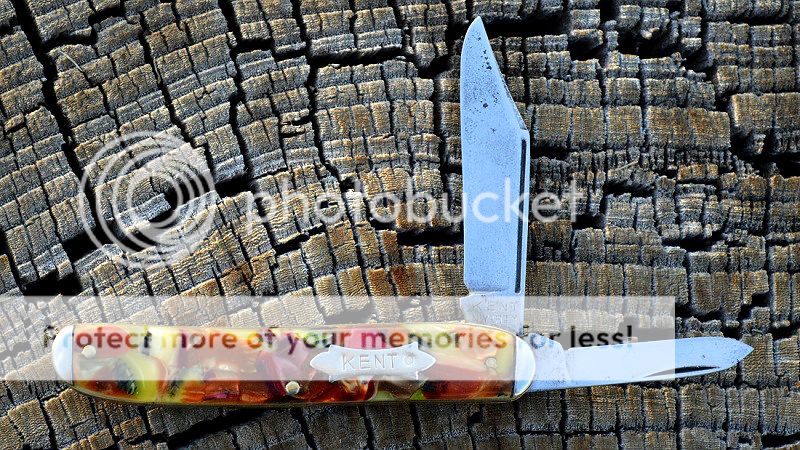

Kent branded pocket knives sold quite well and for many years. They were well made and yet inexpensive. Some of the designs were quite handsome and colorful. Some were utilitarian in stagged plastics. Almost all were a good value for the price at a time when Americans counted their pennies closely.

Here is the earliest Kent Sportsman’s sheath knife I have. Tom Williams couldn’t recall the pattern number, but knew that it predated 1939. Cocobolo wood handle with brass pins, full tang high carbon steel blade.

The Kent fixed hunting blades seem to be less common, far more so than the various patterns of slipjoints.

Here is the next Camillus Sportsman’s pattern, #5665, which was introduced in 1939 according to Tom Williams. Stagged bone handles, brass rivets, added guard, chrome plated with special blade etch:

While it is a decent example of the pattern, it is quite shelf worn and the etch is hard to read. Here is the upgrade I just bought to replace it in my collection. Viva la difference!

I take it that Woolworth's did not buy and sell a lot of fixed blade hunting knives. Price point, maybe. According to the late John Goins, the Kent branded knives date 1931-1955, which may or may not be precise. Why/how did they quit selling them? Perhaps they just quit having them private branded and sold manufacturer branded knives for a while after circa 1955. Baer stated that his Ulster made some knives for Woolworths, and he sold them some Imperials later too. In the late 1950’s to early 1960’s Woolworth’s, like Kresge (K-Mart) and several other five-and-dimes moved into a newer market of a larger variety store.

As a side note, Woolworth’s is I believe one of the largest food supermarket chains in Australia, and is still doing well in England and Germany. In America, they are now Footlocker, Inc. having bankrupted in the late 1990’s and owning Kennys Shoes.

I find that knowing the story behind a knife makes collecting and ownership more enjoyable. Sometimes we luck out and get the personal story of first purchase and ownership from the original buyer, but most often not. Then it takes a bit of sleuthing to get the full story, particularly with privately branded knives (SFO’s or “Special Factory Orders”

Over the past few years I bought several patterns of these inexpensive folders just to explore the materials and construction. The stamping is currently not very popular among those who know, or don’t know it’s origins, much like the Sears Craftsman knives were a few years ago, so one can often pick these up at very reasonable prices. The marking is KENT - N.Y. CITY - U.S.A.

Now, most of us know that few, if any knives were actually manufactured in New York City, though there did exist a section of one street known as “Cutler’s Row” where many importers, jobbers, and manufacturers had their offices located.

When we look up the mark in Goins Encyclopedia Of Cutlery Markings (1998), we see that he attributes the mark to A. Kastor & Brothers (Camillus) as used on knives manufactured circa 1931-1955 for F. W. Woolworth.

As with Sears Roebuck & Company, F. W. Woolworths was the brainchild of one merchant pioneer who based his store on a successful formula. Frank Winfield Woolworth (1852-1919) was the originator of "five-and-ten-cent" stores.

Frank was a farm boy in upstate New York who began his merchant career as a clerk in a drygoods store in Watertown New York From a website archive:

In 1873, he started working in a drygoods store in Watertown, New York. He worked for free for the first three months, because the owner claimed "why should I pay you for teaching the business". He remained there for 6 years. There he observed a passing fad: Leftover items were priced at five cents and placed on a table. Woolworth liked the idea, so he borrowed $300 to open a store where all items were priced at five cents.

Impressed with the success of a five-cent clearance sale, he conceived the novel idea of establishing a store to sell a variety of items in volume at that price. With $300 in inventory advanced to him by his employer, Woolworth started a small store in Utica in 1879, but it soon failed. By 1881, however, Woolworth had two successful stores operating in Pennsylvania. By adding ten-cent items, he was able to increase his inventory greatly and thereby acquired a unique institutional status most important for the success of his stores.

Woolworth's first five-cent store, established in Utica, New York on February 22, 1879, failed within weeks. At his second store, established in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in April 1879, he expanded the concept to include merchandise priced at ten cents. The second store was successful, and Woolworth and his brother, Charles Sumner Woolworth, opened a large number of five-and-ten-cent stores. His original employer was made a partner.

The growth of Woolworth's chain was rapid. Capital for new stores came partly from the profits of those already in operation and partly from investment by partners whom Woolworth installed as managers of the new units. Initially, many of the partners were Woolworth's relatives and colleagues.

Convinced that the most important factor in ensuring the success of the chain was increasing the variety of goods offered, Woolworth in 1886 moved to Brooklyn, New York, to be near wholesale suppliers. He also undertook the purchasing for the entire chain. A major breakthrough came when he decided to stock candy and was able to bypass wholesalers and deal directly with manufacturers. Aware of the importance of the presentation of goods, Woolworth took the responsibility for planning window and counter displays for the whole chain and devised the familiar red store front which became its institutional hallmark.

The success of the chain between 1890 and 1910 was phenomenal. The company had 631 outlets doing a business of $60,558,000 annually by 1912. In that year Woolworth merged with five of his leading competitors, forming a corporation capitalized at $65 million. The next year, at a cost of $13.5 million, he built the Woolworth Building in downtown New York, the tallest skyscraper in the world at the time. Cass Gilbert was the architect, and it was engineered by Gunvald Aus. Another rare fact about the Woolworth Building -- it served as the company's headquarters right up until Woolworth's 1997 declaration of bankruptcy. By 1997, the original chain he founded had been reduced to 400 stores, and other divisions of the company began to be more profitable than the original chain. The original chain went out of business on July 17th, 1997, as the firm began its transition into Foot Locker, Inc.

The UK stores continued operating (albeit under separate ownership since 1982) after the US operation ceased under the Woolworth name and now trade as Woolworths.

Vital statistics 1929

total annual sales in the US and Canada $272,754,045

11,000 bales of cotton used to weave towels alone, with 2,000 looms working 24 hours a day and employing 1,000 people

over a million mousetraps sold every year

100,000,000 shaves with Woolworths blades during 1929

over 1,000,000 nets and 5,000,000 printed curtains sold

7,500,000 tons of yarn used to make men's socks

90,000,000 lunches served to customers during the year

4,000 miles of pencils if laid end to end and 300 miles of pen points

33,000 miles of garter elastic

1929? Why would I back this up to mention 1929?

Well, many retailers and manufacturers bit the big one in the Great Depression of 1929-1932. The list of cutlerys and hardware jobbers which closed is large.

1929: Remington sold out to the Dupont Company.

1930: Schatt-Morgan Knife Company filed for bankruptcy.

1931: New York Knife Company went out of business, the factory was closed due to bankruptcy.

However, some not only survived but thrived. Woolworth's and A. Kastor & Brothers / Camillus were such companies. Their success was largely due to innovative thinkers able to meet a vastly changed marketing landscape.

Circa 1931-1955...? Oh, how can I tell a story of the American knife industry without mentioning Albert Baer!

Albert M. Baer was put in charge of sales in 1930. Albert signed George Herman ‘Babe’ Ruth to endorse autographed baseball bat figural knife for Kastor Bros., first of many endorsements. In order to permit Baer to be a stockholder, Alfred B. Kastor sold him 50 shares of his common stock

Under Baer's management of sales, Camillus manufactured KENT brand knives for F.W. Woolworth's beginning in 1931.

Excerpts from the A.M.Baer Memoirs:

"My habit was to go to the Woolworth Company every Christmas and every New Year and thank them for the business they gave us. This started in 1923 because I got the inspiration that any company with the number of stores that Woolworth had, should be the outlet for the products that we made at Camillus Cutlery, regardless of the fact they had a limit of 10 cents in the east, and 15 cents in the west.

George's predecessor, Mr. P. G. Franz, lived in Buck Hill, Pennsylvania, and he had an apartment at 86th Street and Central Park West. He traveled to Europe regularly to their main headquarters in Crayfell, Germany and was punctilious about never going to lunch with anybody or not even accepting a book when he sailed on the Europa. P.G. liked me and although I had practically nothing to sell, I still called on him and was particularly fond of his assistant, a woman 10 years my senior, named Mrs. Kissack. Mrs. Kissack always tipped me off when I phoned for an appointment as to whether P.G. was in good mood or not. All the years I called on him, he called me "Mr. Baer" and he was always "Mr. Franz." One day Alfred Kastor showed me a sample of a two-blade metal handle Jackknife that

Mr. Gerling had sent us, and quoted us 3 cents a dozen. Now the tariff on importing knives advanced considerably with knives when sold at over 39 a dozen both ad valorem and specific. If you don't know customs terms, ad valorem is a percentage of the value and specific is a set amount per knife. 3~ knives, FOB Germany, landed in this country at about

57. I never asked Alfred anything but took the samples down to P.G., told him what we paid for them, where we bought them. He knew Gerling and P. G. wrote up a general order to be shipped to all stores for 10,000 gross. Big deal! He paid me 85 a dozen. I brought the order back to the office and I thought Alfred would flip. He practically made a special trip to Germany and placed the order, and we were in business with Woolworth selling them 10 cent pocket knives. They sold like hot cakes and in the midst of the sale, over the Wall Street ticker, came word that Woolworth was about to sell 20 cent merchandise. Here was the opportunity of a lifetime. Now we could make a Camillus product in the USA and boy, we needed the business. I was down to see Franz the same day word came out, and he agreed that we should submit some samples, for he said he wanted to get prices and samples from other factories, particularly a company in Providence called Imperial, for they had been trying to make 10 cent knives in the United States for him and he heard that they gave good value.

I had no sooner returned to my office that I had a phone call from him asking me to come back. When I did, he was shaking with anger. "What do you think?" he said. “The American Cutlery Industry, led by Domenic Fazzano of Imperial have lodged a complaint claiming that the 10 cent knives which you sold me were undervalued, and we have to go to Customs Court to fight the case. How dare they on one hand come to try to sell me, and on the other hand act in this underhanded way?"

I told P.G. not to worry. We had done nothing illegal. We would stand behind him and Woolworth and fight this case. I suggested that he get two samples from Imperial as though nothing had happened, so we would see what they were going to offer competitors. He smiled and said “Wonderful. We’ll, fight fire with fire! “ It was not long before we had the sample roll of the 10 knives Imperial had submitted to the Woolworth Company. I took the knives to the factory. We discussed the quantities involved, took the prices that Imperial had quoted Franz and duplicated the patterns as best as we could, and down I went to see P.G. I got him to pay us a little bit more than

Imperial because we made a better product. He paid us $1.505 a dozen and he sold them for 20 cents each.

When the knives hit the stores, they were a sensation. The sales were enormous. You could go and count how many they sold per hour. In fact, I did just that, and we started to mechanize the Camillus factory as a result of the Woolworth order. P.G. never told Imperial why they lost the business, for certainly had Domenic not been part of the conspiracy to embarrass me, they would have had this business.

The hearing in the Customs Court took place, and we were able to prove that there was no chicanery. The case was dismissed and with tears in his eyes, P.G. Franz looked at me and said “As long as you live, Mr. Baer, we will let you be competitive, and if you meet competition, you will always have our business.” This message he passed on to George Graff and for all the years that I was with Camillus, George lived up to P.G.’s admonition. When George Graff became the buyer of Woolworth, I was selling several knives to him. George seemed like a nice guy. He came out of the Chicago district office. He knew about and liked ..to sell pocket knives...

And in fact, when George Graff did take over as the buyer for Woolworth, he continued buying from Baer. And then in October 1940, Baer left Camillus in a tiff with the Kastor brothers. And most of the buyers, Sears’ Col. Tom Dunlap and Woolworth's George Graff included, followed Albert to his new company, Ulster. Another excerpt:

George Graff, the Wool-worth buyer, wrote a letter to the Board that Camillus was a ship without a rudder. That didn't sit well with Alfred Kastor, for F. W. Woolworth was their #2 client.

Kent branded pocket knives sold quite well and for many years. They were well made and yet inexpensive. Some of the designs were quite handsome and colorful. Some were utilitarian in stagged plastics. Almost all were a good value for the price at a time when Americans counted their pennies closely.

Here is the earliest Kent Sportsman’s sheath knife I have. Tom Williams couldn’t recall the pattern number, but knew that it predated 1939. Cocobolo wood handle with brass pins, full tang high carbon steel blade.

The Kent fixed hunting blades seem to be less common, far more so than the various patterns of slipjoints.

Here is the next Camillus Sportsman’s pattern, #5665, which was introduced in 1939 according to Tom Williams. Stagged bone handles, brass rivets, added guard, chrome plated with special blade etch:

While it is a decent example of the pattern, it is quite shelf worn and the etch is hard to read. Here is the upgrade I just bought to replace it in my collection. Viva la difference!

I take it that Woolworth's did not buy and sell a lot of fixed blade hunting knives. Price point, maybe. According to the late John Goins, the Kent branded knives date 1931-1955, which may or may not be precise. Why/how did they quit selling them? Perhaps they just quit having them private branded and sold manufacturer branded knives for a while after circa 1955. Baer stated that his Ulster made some knives for Woolworths, and he sold them some Imperials later too. In the late 1950’s to early 1960’s Woolworth’s, like Kresge (K-Mart) and several other five-and-dimes moved into a newer market of a larger variety store.

As a side note, Woolworth’s is I believe one of the largest food supermarket chains in Australia, and is still doing well in England and Germany. In America, they are now Footlocker, Inc. having bankrupted in the late 1990’s and owning Kennys Shoes.

Last edited: