Sando

Knife Maker

- Joined

- Jul 4, 2002

- Messages

- 1,148

I've been thinking about something for while now. The poll about grinding pre-heat treat got me to share those thoughts. You may find it interesting or feel I'm full of it. But here goes .......

Problem:

At the end of the day, all this heat treat business is about a very teeny, tiny amount of steel. That little sliver we call the edge. We measure the HRC of the blade in general, but what we really hope is that the thinnest bit of steel we sharpen is the hardest part, has the finest grain structure and no flaws.

So my belief is that that most important part of the blade has to be protected at all costs. It has to be hidden from it's 2 biggest enemies: decarborization while heat-treating and over-heating while grinding. I believe that magic sliver needs to be hidden throughout our work as long as possible.

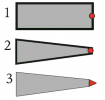

Consider a cross-section look of a blade that was profiled to the final, perfect width. The red circle is the steel that becomes your final edge. The thick black outline is the zone of potential decarb.

Number 1 is heat treated prior to any grinding. Notice that the edge steel has been exposed to potential decarb on one side. Number 2 is pre-ground to near completion before heat-treatment. It's been exposed on three sides!

When you are finished with heat treating, grinding and final polishing, just what is the condition of that bit of steel?

Solution:

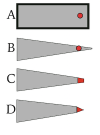

I'd like you to consider thinking of the final edge buried further back from your profiled edge. Like this:

In A we are planning on the edge being 1/16" or so back from where you've profiled it. (If you grind some pre-heat treat, leave it thick enough to protect that edge steel.) In B you grind it down even thinner than what you need. Say you want 0.010" behind the edge. So you grind it down to 0.003" or less (I've been grinding to zero lately). Then in step C you knock it back to the desired thickness. That only takes a pass or two holding the knife vertical on a fine belt or dragging it on a whetstone.

To put it succinctly: Step one, leave the blade a little wider than the final dimension. Step two, grind way thinner than your final edge thickness, then knock it back to where you want.

Now when you sharpen you're working with steel that's had minimal stress.

OK - I'll bet most everybody will say, "Duh. Of course." But it was new to me and I haven't heard it talked about before.

Problem:

At the end of the day, all this heat treat business is about a very teeny, tiny amount of steel. That little sliver we call the edge. We measure the HRC of the blade in general, but what we really hope is that the thinnest bit of steel we sharpen is the hardest part, has the finest grain structure and no flaws.

So my belief is that that most important part of the blade has to be protected at all costs. It has to be hidden from it's 2 biggest enemies: decarborization while heat-treating and over-heating while grinding. I believe that magic sliver needs to be hidden throughout our work as long as possible.

Consider a cross-section look of a blade that was profiled to the final, perfect width. The red circle is the steel that becomes your final edge. The thick black outline is the zone of potential decarb.

Number 1 is heat treated prior to any grinding. Notice that the edge steel has been exposed to potential decarb on one side. Number 2 is pre-ground to near completion before heat-treatment. It's been exposed on three sides!

When you are finished with heat treating, grinding and final polishing, just what is the condition of that bit of steel?

Solution:

I'd like you to consider thinking of the final edge buried further back from your profiled edge. Like this:

In A we are planning on the edge being 1/16" or so back from where you've profiled it. (If you grind some pre-heat treat, leave it thick enough to protect that edge steel.) In B you grind it down even thinner than what you need. Say you want 0.010" behind the edge. So you grind it down to 0.003" or less (I've been grinding to zero lately). Then in step C you knock it back to the desired thickness. That only takes a pass or two holding the knife vertical on a fine belt or dragging it on a whetstone.

To put it succinctly: Step one, leave the blade a little wider than the final dimension. Step two, grind way thinner than your final edge thickness, then knock it back to where you want.

Now when you sharpen you're working with steel that's had minimal stress.

OK - I'll bet most everybody will say, "Duh. Of course." But it was new to me and I haven't heard it talked about before.