-

The BladeForums.com 2024 Traditional Knife is available! Price is $250 ea (shipped within CONUS).

Order here: https://www.bladeforums.com/help/2024-traditional/

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Skinner

- Thread starter mendezj

- Start date

- Joined

- Nov 20, 2011

- Messages

- 5,000

Nathan loves D2. Production of this knife predates Delta 3V heat treat protocol. CPK was just Nathan and Jo when this knife was produced. Much smaller production numbers during this time - as well as less demand at the time.

It is highly sought after and pattern has not been revisited. We have asked nicely multiple times. Someday... maybe. Currently, there are quite a few things on the whiteboard - the skinner isn’t one of them.

It is highly sought after and pattern has not been revisited. We have asked nicely multiple times. Someday... maybe. Currently, there are quite a few things on the whiteboard - the skinner isn’t one of them.

In that role, I see d2 being indistinguishable from d3v while being cheaper and easier to work with.

Skinning isn't a toughness game, it's an edge holding game. And d2 is good at holding an edge. Just not so good at toughness like d3v. But if you are using a skinning knife like a field knife.....you are doing it wrong.

Edit: I'm a fan of d2 in smaller blades that won't be stressed but used frequently for slicing tasks.

Skinning isn't a toughness game, it's an edge holding game. And d2 is good at holding an edge. Just not so good at toughness like d3v. But if you are using a skinning knife like a field knife.....you are doing it wrong.

Edit: I'm a fan of d2 in smaller blades that won't be stressed but used frequently for slicing tasks.

- Joined

- Nov 24, 1998

- Messages

- 993

Thank you for your responses. Indeed, D2 also is all about heat treatment. I have D2 knives from different makers, some famous for their D2, and some are much better than others (and the better ones not necessarily being the “famous” ones). I say “better” when skinning game, as some keep sharp after going through many pieces while the others get dull quickly. I’d like to add my name to the Skinner list.

- Joined

- Sep 29, 2008

- Messages

- 10,394

I’d like to add my name to the Skinner list.

You and me both! It's a lovely looking knife. Sometimes I trawl back in forum history to see Nathan's early works.

woodysone

Gold Member

- Joined

- Nov 21, 2005

- Messages

- 10,592

I was lucky to get a couple of these when he was offering them. Had to scape up the funds but I’m sure glad I did. One had a thinner grind, and remember there were special instructions not to break breast bones it's a skinner. It was “stolen” by my wife early on and has been her meat prep knife since. I’m not complaining as I don’t hunt and get the benefits of her work. It’s been Her go to for the last ten years.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Sep 29, 2008

- Messages

- 10,394

One had a thinner grind, and remember there were special instructions not to break breast bones it a skinner.

Instructions like this make me wonder if I’m under utilizing my knives. I don’t think I’ve ever broken a bone with one. Am I missing out?

Nathan the Machinist

KnifeMaker / Machinist / Evil Genius

Moderator

Knifemaker / Craftsman / Service Provider

- Joined

- Feb 13, 2007

- Messages

- 18,643

It's pretty easy to split the rib cage on a deer and is a common practice while processing it. But I wouldn't recommend it if using an extremely thin knife

- Joined

- May 7, 2012

- Messages

- 4,971

Maybe we ought to gather a list of ten or twenty which might convince Mr. Carothers to bring the Skinner back from the grave.

I’m 99.9999% sure Nathan knows he could sell 100+ of them today if he offered them.

From what I remember which was several years ago now, Nathan doesn’t have the fixtures, or platten or something like that anymore.

His D2 HT is second to none, I can tell you that. I’ve had two of his D2 Skinners. I’d gladly buy a set to use as steak knives at the table.

JJ_Colt45

Platinum Member

- Joined

- Sep 11, 2014

- Messages

- 6,839

You can split the rib cage and even the pelvic bone on a whitetail fairly easily if you know how but as Nathan said I wouldn't recommend using your skinning knife (to save your edge) or a thin blade to be safe.

Of all of Nathan's knives the Skinner is probably the one I most wish I had been around for ... I love to hunt and that type of knife gets used for everything from small game and upland birds to waterfowl and sees some use during deer season. Its one of my favorite type of blades even useful around the dinner table and kitchen. I have used one of my EDC2s to field dress and skin deer and it works great but the blade is a bit tall and short for use on small game and birds. It can be done but I prefer blade more along the lines of the Skinner.

When he gets around to offering something again in that line i will most likely buy multiplies as they would get a lot of use. D2 works for me D3V would work for me as well.

Of all of Nathan's knives the Skinner is probably the one I most wish I had been around for ... I love to hunt and that type of knife gets used for everything from small game and upland birds to waterfowl and sees some use during deer season. Its one of my favorite type of blades even useful around the dinner table and kitchen. I have used one of my EDC2s to field dress and skin deer and it works great but the blade is a bit tall and short for use on small game and birds. It can be done but I prefer blade more along the lines of the Skinner.

When he gets around to offering something again in that line i will most likely buy multiplies as they would get a lot of use. D2 works for me D3V would work for me as well.

- Joined

- Sep 29, 2008

- Messages

- 10,394

It's pretty easy to split the rib cage on a deer and is a common practice while processing it. But I wouldn't recommend it if using an extremely thin knife

I never went hunting before I moved and I regret not making it a higher priority. How thin exactly is extremely thin to you?

- Joined

- Mar 20, 2016

- Messages

- 14,376

During my tenure in here as the former court jester to the Court of King Nathan, there's been a trifecta of OG-CPKs which I've never had the pleasure of handling which in most likelihood will never see in person: 10" Dagger, Potato Knife and the Skinner. It's OK though, I'll manage to live on without!

Last edited:

Nathan the Machinist

KnifeMaker / Machinist / Evil Genius

Moderator

Knifemaker / Craftsman / Service Provider

- Joined

- Feb 13, 2007

- Messages

- 18,643

I never went hunting before I moved and I regret not making it a higher priority. How thin exactly is extremely thin to you?

Some of the skinners were around .010" at the edge, ground above tangent (like a straight razor) and sharpened around 13 DPS in hard D2. They would flex some over your thumb nail and a couple would ring a little when stropped. They'd pop a free standing hair and would slice through meat and hide like a light saber. When pulling the hide off the rib cage there's a few little muscles that attach the skin to the flanks that you sometime need to cut or they'll tear meat that you may or may not care about. These could be severed while under tension with a tiny little tap of the blade. When pulling the intestines and other bits from inside the pelvis (I don't cut these, I tie them off) there are bits of connective tissue holding them in place than could be severed with the lightest touch of the blade. I'd hold the butt of the handle in the palm of my hand and extend the blade out along my index finger like an extension of the finger and disconnect bits without pulling on them like a magic wand. These blades were sharp and stayed sharp though an entire season of use (no need to resharpen during a hunt) but you did not want to use one to split a rib cage or pelvis, they weren't built for that and you'd loose a chunk out of the blade.

I don't really skin a deer with a skinning knife so the name is a misnomer. The real work is done by hand (or if you're prone to hand cramps, plyers). There is a cut around the anus and reproductive bits (which get tied off) and cuts along the belly and down the front of the rear legs, but the rest of the skin is simply pulled free by hand or with a pair of plyers with little use of a knife. The skinning knife is used to make these initial cuts held edge out, controlling the depth of cut with the angle of the drop point. Once the hide starts cutting it feeds itself over the edge. Once you learn to unzip a deer this way you'll never want to use a clumsy gut hook again. Gut hooks can bunch up the hide and get hair on the meat. Other than the initial cuts, the skinning knife isn't really used much for skinning, but it is used to process the deer in the field. After the initial cuts in the skin the real use is cutting tendons pulling out the major muscle groups and cutting though fascia and connective tissue around joints. I leave the pelvis on the carcass so I need to separate the femur from the hip which requires cutting the hams free of the pelvis and lower spine and slipping the blade into the ball socket of the femur and cutting a tendon connecting the two inside of the joint. The front legs are easily cut free from the carcass by pulling the shoulder blades and cutting all the little tendons (there's surprising little holding a front leg on). The "back strap" is the real prize on a deer. This is the New York strip and it's large, tender and tasty. But you have to cut it free of the spine in a bunch of places. Substantial bone contact is unavoidable along the spine and this is one of the things that led me on my edge stability jihad. The tender loin is two small muscles on both side of the spine on the inside wall of the carcass which is easily bruised and torn if handled roughly. There are lymph nodes here you want to separate without disturbing them. A skinning knife that is more of a scalpel is helpful here. There's a gland in the rear legs too, hidden between a couple muscle groups. When using a thin fragile blade I don't bother splitting the rib cage or the pelvis, they're discarded in place. Unless you're into organ meat there's really nothing inside of the rib cage worth messing with. No need to remove the head either so I leave the skin attached at the neck. It's worth noting that with some practice you can pull the skin off the deer in a few minutes, and pull the meat off in about 10-20 minutes and get it chilled quickly, and at no point is the digestive, reproductive or excretory system ever actually cut. On an animal held upside down from its Achilles tendons it's possible to put your chum bucket under the deer and drop everything down into the bucket but leave it attached, remove the meat and discard the rest without disturbing it. I almost always shoot the brain rather than heart/lungs (the accuracy required to do this reliably is what led me into reloading and bench rest shooting because when Jo and I lived in Georgia some of these head shots were 200 yards) so the process is actually pretty quick and tidy. If I'm carful to avoid getting hair on the meat I've found that I can pack my deer in plastic in the cooler without even needing to rinse anything. I have neat tidy sections ready to age laid out in the old beer fridge. All of this is what led me to make my D2 skinners, because I hadn't found a knife with all of the attributes that I wanted (blade shape and geometry and edge retention), and lead to the heat treat optimizations for that D2 (these optimizations are widely adopted in the industry now, but were considered blasphemy back when I was first developing them 20 years ago) and in a round about sort of way this is all what started us out down this path we're on now. I had a little machine shop and I did small tool and die work at the time so I already had a heat treat oven and was doing heat treat but it was conversations with Cliff Stamp and Alvin Johnson over at rec.knives that lead me down the heat treat rabbit hole 20 years ago and I'm glad I listened to them and started experimenting outside of the box by utilizing a rapid quench and a quench to ~.100 to address retained austenite rather than needing to utilize the secondary hardening hump. <-- that's where it all started and that was these D2 skinners. A lot of history there.

Last edited:

woodysone

Gold Member

- Joined

- Nov 21, 2005

- Messages

- 10,592

Sure is a lot of history here, all I know is it cuts like the dickens and the edge lasts a long time. Thank you Nathan! Your work has been appreciated .Some of the skinners were around .010" at the edge, ground above tangent (like a straight razor) and sharpened around 13 DPS in hard D2. They would flex some over your thumb nail and a couple would ring a little when stropped. They'd pop a free standing hair and would slice through meat and hide like a light saber. When pulling the hide off the rib cage there's a few little muscles that attach the skin to the flanks that you sometime need to cut or they'll tear meat that you may or may not care about. These could be severed while under tension with a tiny little tap of the blade. When pulling the intestines and other bits from inside the pelvis (I don't cut these, I tie them off) there are bits of connective tissue holding them in place than could be severed with the lightest touch of the blade. I'd hold the butt of the handle in the palm of my hand and extend the blade out along my index finger like an extension of the finger and disconnect bits without pulling on them like a magic wand. These blades were sharp and stayed sharp though an entire season of use (no need to resharpen during a hunt) but you did not want to use one to split a rib cage or pelvis, they weren't built for that and you'd loose a chunk out of the blade.

I don't really skin a deer with a skinning knife so the name is a misnomer. The real work is done by hand (or if you're prone to hand cramps, plyers). There is a cut around the anus and reproductive bits (which get tied off) and cuts along the belly and down the front of the rear legs, but the rest of the skin is simply pulled free by hand or with a pair of plyers with little use of a knife. The skinning knife is used to make these initial cuts held edge out, controlling the depth of cut with the angle of the drop point. Once the hide starts cutting it feeds itself over the edge. Once you learn to unzip a deer this way you'll never want to use a clumsy gut hook again. Gut hooks can bunch up the hide and get hair on the meat. Other than the initial cuts, the skinning knife isn't really used much for skinning, but it is used to process the deer in the field. After the initial cuts in the skin the real use is cutting tendons pulling out the major muscle groups and cutting though fascia and connective tissue around joints. I leave the pelvis on the carcass so I need to separate the femur from the hip which requires cutting the hams free of the pelvis and lower spine and slipping the blade into the ball socket of the femur and cutting a tendon connecting the two inside of the joint. The front legs are easily cut free from the carcass by pulling the shoulder blades and cutting all the little tendons (there's surprising little holding a front leg on). The "back strap" is the real prize on a deer. This is the New York strip and it's large, tender and tasty. But you have to cut it free of the spine in a bunch of places. Substantial bone contact is unavoidable along the spine and this is one of the things that led me on my edge stability jihad. The tender loin is two small muscles on both side of the spine on the inside wall of the carcass which is easily bruised and torn if handled roughly. There are lymph nodes here you want to separate without disturbing them. A skinning knife that is more of a scalpel is helpful here. There's a gland in the rear legs too, hidden between a couple muscle groups. When using a thin fragile blade I don't bother splitting the rib cage or the pelvis, they're discarded in place. Unless you're into organ meat there's really nothing inside of the rib cage worth messing with. No need to remove the head either so I leave the skin attached at the neck. It's worth noting that with some practice you can pull the skin off the deer in a few minutes, and pull the meat off in about 10-20 minutes and get it chilled quickly, and at no point is the digestive, reproductive or excretory system ever actually cut. On an animal held upside down from its Achilles tendons it's possible to put your chum bucket under the deer and drop everything down into the bucket but leave it attached, remove the meat and discard the rest without disturbing it. I almost always shoot the brain rather than heart/lungs (the accuracy required to do this reliably is what led me into reloading and bench rest shooting because when Jo and I lived in Georgia some of these head shots were 200 yards) so the process is actually pretty quick and tidy. If I'm carful to avoid getting hair on the meat I've found that I can pack my deer in plastic in the cooler without even needing to rinse anything. I have neat tidy sections ready to age laid out in the old beer fridge. All of this is what led me to make my D2 skinners, because I hadn't found a knife with all of the attributes that I wanted (blade shape and geometry and edge retention), and lead to the heat treat optimizations for that D2 (these optimizations are widely adopted in the industry now, but were considered blasphemy back when I was first developing them 20 years ago) and in a round about sort of way this is all what started us out down this path we're on now. I had a little machine shop and I did small tool and die work at the time so I already had a heat treat oven and was doing heat treat but it was conversations with Cliff Stamp and Alvin Johnson over at rec.knives that lead me down the heat treat rabbit hole 20 years ago and I'm glad I listened to them and started experimenting outside of the box by utilizing a rapid quench and a quench to ~.100 to address retained austenite rather than needing to utilize the secondary hardening hump. <-- that's where it all started and that was these D2 skinners. A lot of history there.

- Joined

- Nov 24, 1998

- Messages

- 993

Some of the skinners were around .010" at the edge, ground above tangent (like a straight razor) and sharpened around 13 DPS in hard D2. They would flex some over your thumb nail and a couple would ring a little when stropped. They'd pop a free standing hair and would slice through meat and hide like a light saber. When pulling the hide off the rib cage there's a few little muscles that attach the skin to the flanks that you sometime need to cut or they'll tear meat that you may or may not care about. These could be severed while under tension with a tiny little tap of the blade. When pulling the intestines and other bits from inside the pelvis (I don't cut these, I tie them off) there are bits of connective tissue holding them in place than could be severed with the lightest touch of the blade. I'd hold the butt of the handle in the palm of my hand and extend the blade out along my index finger like an extension of the finger and disconnect bits without pulling on them like a magic wand. These blades were sharp and stayed sharp though an entire season of use (no need to resharpen during a hunt) but you did not want to use one to split a rib cage or pelvis, they weren't built for that and you'd loose a chunk out of the blade.

I don't really skin a deer with a skinning knife so the name is a misnomer. The real work is done by hand (or if you're prone to hand cramps, plyers). There is a cut around the anus and reproductive bits (which get tied off) and cuts along the belly and down the front of the rear legs, but the rest of the skin is simply pulled free by hand or with a pair of plyers with little use of a knife. The skinning knife is used to make these initial cuts held edge out, controlling the depth of cut with the angle of the drop point. Once the hide starts cutting it feeds itself over the edge. Once you learn to unzip a deer this way you'll never want to use a clumsy gut hook again. Gut hooks can bunch up the hide and get hair on the meat. Other than the initial cuts, the skinning knife isn't really used much for skinning, but it is used to process the deer in the field. After the initial cuts in the skin the real use is cutting tendons pulling out the major muscle groups and cutting though fascia and connective tissue around joints. I leave the pelvis on the carcass so I need to separate the femur from the hip which requires cutting the hams free of the pelvis and lower spine and slipping the blade into the ball socket of the femur and cutting a tendon connecting the two inside of the joint. The front legs are easily cut free from the carcass by pulling the shoulder blades and cutting all the little tendons (there's surprising little holding a front leg on). The "back strap" is the real prize on a deer. This is the New York strip and it's large, tender and tasty. But you have to cut it free of the spine in a bunch of places. Substantial bone contact is unavoidable along the spine and this is one of the things that led me on my edge stability jihad. The tender loin is two small muscles on both side of the spine on the inside wall of the carcass which is easily bruised and torn if handled roughly. There are lymph nodes here you want to separate without disturbing them. A skinning knife that is more of a scalpel is helpful here. There's a gland in the rear legs too, hidden between a couple muscle groups. When using a thin fragile blade I don't bother splitting the rib cage or the pelvis, they're discarded in place. Unless you're into organ meat there's really nothing inside of the rib cage worth messing with. No need to remove the head either so I leave the skin attached at the neck. It's worth noting that with some practice you can pull the skin off the deer in a few minutes, and pull the meat off in about 10-20 minutes and get it chilled quickly, and at no point is the digestive, reproductive or excretory system ever actually cut. On an animal held upside down from its Achilles tendons it's possible to put your chum bucket under the deer and drop everything down into the bucket but leave it attached, remove the meat and discard the rest without disturbing it. I almost always shoot the brain rather than heart/lungs (the accuracy required to do this reliably is what led me into reloading and bench rest shooting because when Jo and I lived in Georgia some of these head shots were 200 yards) so the process is actually pretty quick and tidy. If I'm carful to avoid getting hair on the meat I've found that I can pack my deer in plastic in the cooler without even needing to rinse anything. I have neat tidy sections ready to age laid out in the old beer fridge. All of this is what led me to make my D2 skinners, because I hadn't found a knife with all of the attributes that I wanted (blade shape and geometry and edge retention), and lead to the heat treat optimizations for that D2 (these optimizations are widely adopted in the industry now, but were considered blasphemy back when I was first developing them 20 years ago) and in a round about sort of way this is all what started us out down this path we're on now. I had a little machine shop and I did small tool and die work at the time so I already had a heat treat oven and was doing heat treat but it was conversations with Cliff Stamp and Alvin Johnson over at rec.knives that lead me down the heat treat rabbit hole 20 years ago and I'm glad I listened to them and started experimenting outside of the box by utilizing a rapid quench and a quench to ~.100 to address retained austenite rather than needing to utilize the secondary hardening hump. <-- that's where it all started and that was these D2 skinners. A lot of history there.

Oops, please see below.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Sep 29, 2008

- Messages

- 10,394

Excellent explanation. It delivered a great mental picture. Thanks!

Choked up with a finger on the spine is how I'm very often using a knife. In the past few years I've leaned to smaller folders because of this.

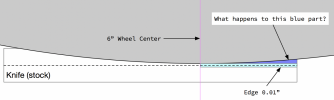

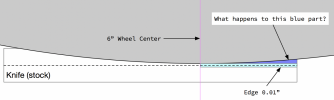

How far above tangent? Enough to require a secondary grind to hit the bevel? I took a few minutes to diagram what I'm asking, this has exaggerated dimensions.

I'd hold the butt of the handle in the palm of my hand and extend the blade out along my index finger like an extension of the finger and disconnect bits without pulling on them like a magic wand.

Choked up with a finger on the spine is how I'm very often using a knife. In the past few years I've leaned to smaller folders because of this.

Some of the skinners were around .010" at the edge, ground above tangent (like a straight razor) and sharpened around 13 DPS in hard D2.

How far above tangent? Enough to require a secondary grind to hit the bevel? I took a few minutes to diagram what I'm asking, this has exaggerated dimensions.

- Joined

- Nov 24, 1998

- Messages

- 993

Such great post. Thank you so much. Indeed, the back straps and the smaller tender loins is what I keep for myself. And I also shoot to the brain. I do use a knife for removing the skin and muscles, but for rib cage, etc., I have an old worn small machete.

In any case, for birds and lake fishing, as well as for deer, a knife like your Skinner is perfect. I’d take two, please

In any case, for birds and lake fishing, as well as for deer, a knife like your Skinner is perfect. I’d take two, please

Nathan the Machinist

KnifeMaker / Machinist / Evil Genius

Moderator

Knifemaker / Craftsman / Service Provider

- Joined

- Feb 13, 2007

- Messages

- 18,643

A 10-in wheel with tangent probably 1/8 of an inch above the edge, so nothing so pronounced as that