I pick up an occasional piece of wrought. Mostly from wagon of farm implements. It's not always easy to identify unless heavily rusted. This guy is verifying wrought iron tires. And not all wagon tires were wrought either.Finally my silly internet connection allowed me to see these photos...Cool thread,thank you all,Steve's historic research is great as usual ,careful and thorough...

This axe is most definitely a composite,a softer body with the steel edge and cap of poll welded on.You can see that on the 4th photo,on the close-up of poll.(3rd photo,of the back(unbeveled)side one may or may not discern the weld...it should be visible in person.Steel is always(almostdarker;and it looks like it's fairly close to the edge. g. the tool is worn some).

So the body of that axe was forged of a malleable,lower-C iron,that in itself wasn't heat-treatable as an edge material.Then it had a higher Carbon edge and poll-plate forge-welded on,that is for certain.

But that's all we can say.I'm afraid that the nature of either of these alloys cannot be further specified,Nor,any dating done on this basis.

Edges from higher-C containing steel were laminated onto tools well into 20th century(unto today,really if you consider carbide-tipped products and all bi-metal blades currently).

Also,Wrought Iron is a slippery term to use,as it meant a number of slightly different things in different historic periods,often non-metallurgically specific;but yet sometimes very specific,like "Single(double,triple,et c. unto 5-times)-Refined Wrought iron",a very perticular Architectural grade...But there were many different kinds of iron used in tool building,and their designation was also diverse...Swedish iron,et c.

But in a Very general sense,Square_peg is very right in that it was very different from Bessemer steel by being non-homogeneous.But for dating,again,it does very little if anything.

Wrought iron was produced in the U.S. until 1969,when the last production ceased.

-

The BladeForums.com 2024 Traditional Knife is ready to order! See this thread for details: https://www.bladeforums.com/threads/bladeforums-2024-traditional-knife.2003187/

Price is$300$250 ea (shipped within CONUS). If you live outside the US, I will contact you after your order for extra shipping charges.

Order here: https://www.bladeforums.com/help/2024-traditional/ - Order as many as you like, we have plenty.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

J.UNDERHILL D.SIMMONS Broad Axe

- Thread starter the-accumulator

- Start date

Square_peg

Gold Member

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2012

- Messages

- 13,832

Good video!

the-accumulator

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 906

Great video but the technique is a little bit hard on the object being tested, however, it would work well for determining the make-up of a supply of scrap was that you were about to re-purpose.

Getting back to the material used in making my Underhill/Simmons axe, I've been studying all the info and expertise that has been shared in this thread and found it rather fascinating. I didn't realize that there were so many possibilities for what materials and combinations could go into the making of an edge tool.

I also appreciate the fact that only I have had the privilege of examining the specimen in question with the naked eye; everyone else has had to rely on my mediocre photographic efforts. I wish you could all sit down with me, have a beer (I'm buying!) and pass this axe around for a closer examination. I think you might find that some of the conclusions that have been drawn have been the result of bad lighting or angles in my photos.

Upon my reexamination of the blade, I can't see any distinct demarcation indicating the use of two different kinds of steel or iron in its make-up. The third photo certainly appears to present the appearance that a cap was welded onto the poll. I'm afraid, however, that my cleaning process has falsely lead to that conclusion. Parallel to the flat surface of the poll, there was a bit of a concavity, perhaps due to some slight mushrooming, and, when I cleaned it, I had to aggressively rub with 150 grit sand paper through that trough. I think that lead to the appearance of two different metals being joined when that might not be the case.

I spent the last day or two examining blades (food choppers) that I'm sure have blades of one material welded to frames of another. Please check these photos:

,

,

,

,

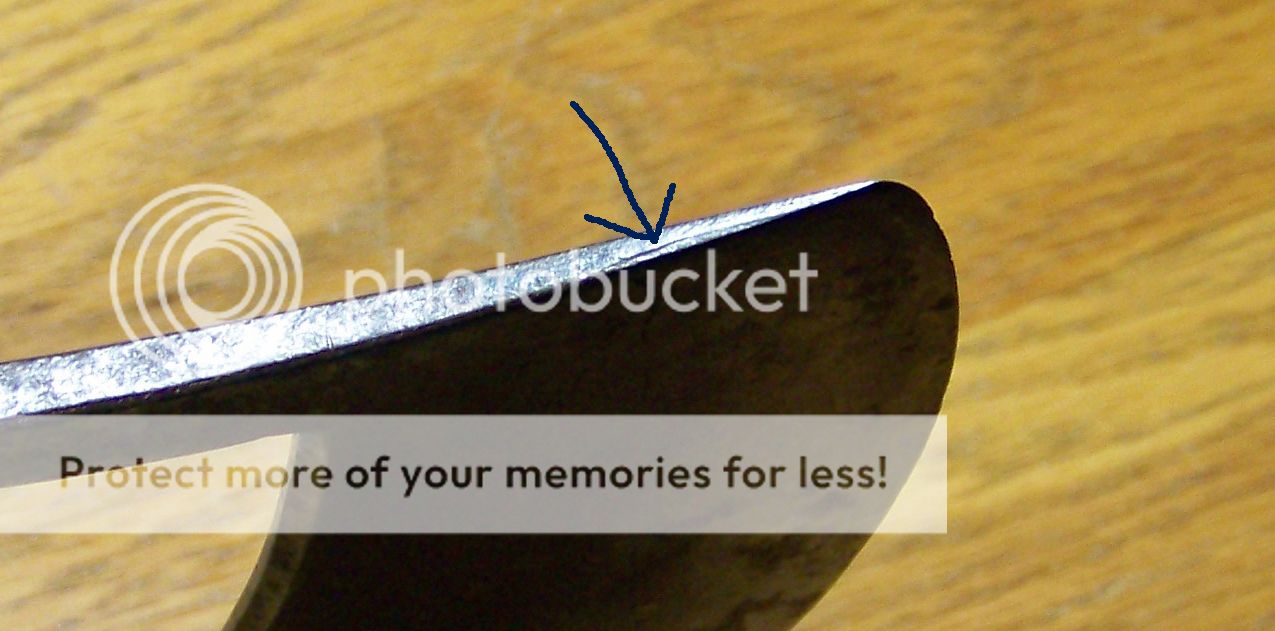

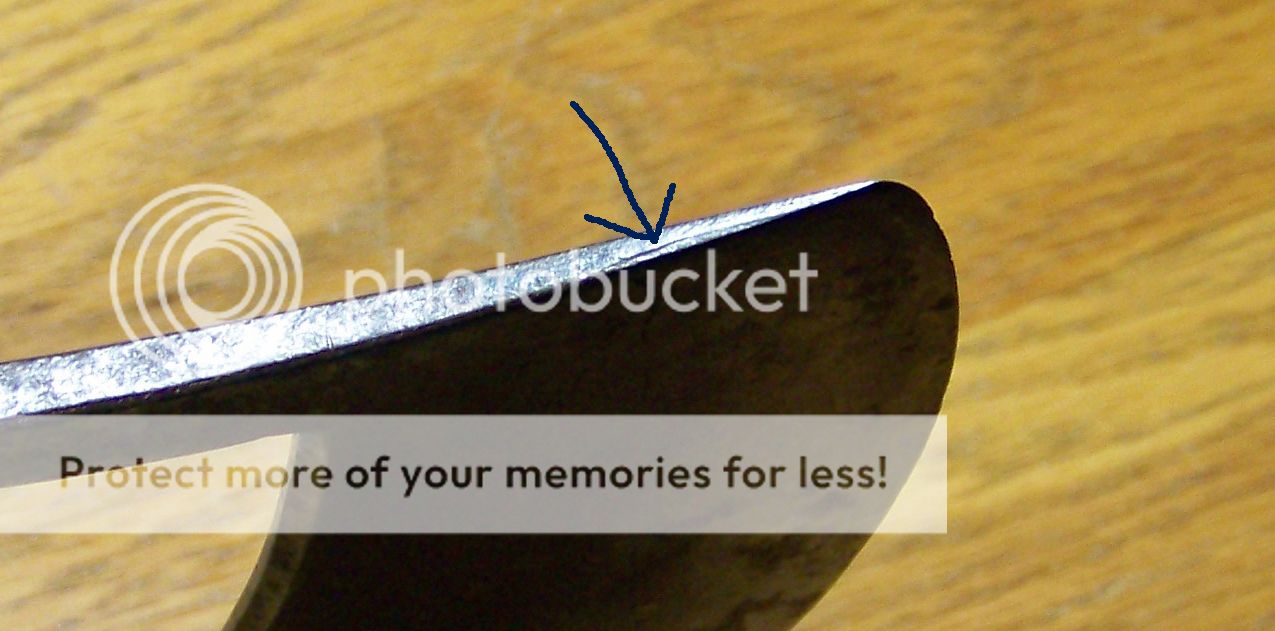

The second photo is of a Swedish chopper with obvious forge welds joining a blade of one material to a frame of another. The two metals have very different colors and surface qualities. The first and third are of a no-name that appears to have a bit sandwiched into a frame of a different material. The photo of the edge shows at the arrow a forge weld that is much more obvious to the naked eye.

Now I'm no expert, and I might be missing something that more experienced eyes might see when examining my axe, but I can't convince myself that there is more than one type of metal there. Maybe I just don't know what to look for??

Again, I can't say enough how much I appreciate the time, effort and expertise you have all put into this discussion. Thank you much. T-A

Getting back to the material used in making my Underhill/Simmons axe, I've been studying all the info and expertise that has been shared in this thread and found it rather fascinating. I didn't realize that there were so many possibilities for what materials and combinations could go into the making of an edge tool.

I also appreciate the fact that only I have had the privilege of examining the specimen in question with the naked eye; everyone else has had to rely on my mediocre photographic efforts. I wish you could all sit down with me, have a beer (I'm buying!) and pass this axe around for a closer examination. I think you might find that some of the conclusions that have been drawn have been the result of bad lighting or angles in my photos.

Upon my reexamination of the blade, I can't see any distinct demarcation indicating the use of two different kinds of steel or iron in its make-up. The third photo certainly appears to present the appearance that a cap was welded onto the poll. I'm afraid, however, that my cleaning process has falsely lead to that conclusion. Parallel to the flat surface of the poll, there was a bit of a concavity, perhaps due to some slight mushrooming, and, when I cleaned it, I had to aggressively rub with 150 grit sand paper through that trough. I think that lead to the appearance of two different metals being joined when that might not be the case.

I spent the last day or two examining blades (food choppers) that I'm sure have blades of one material welded to frames of another. Please check these photos:

,

, ,

,

The second photo is of a Swedish chopper with obvious forge welds joining a blade of one material to a frame of another. The two metals have very different colors and surface qualities. The first and third are of a no-name that appears to have a bit sandwiched into a frame of a different material. The photo of the edge shows at the arrow a forge weld that is much more obvious to the naked eye.

Now I'm no expert, and I might be missing something that more experienced eyes might see when examining my axe, but I can't convince myself that there is more than one type of metal there. Maybe I just don't know what to look for??

Again, I can't say enough how much I appreciate the time, effort and expertise you have all put into this discussion. Thank you much. T-A

Last edited:

the-accumulator

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 906

Ooops! My photos are not in the right order. The first and third are of the no-name with the edge sandwiched into the frame. The second photo is of the Swedish chopper. Sorry for the confusion. T-A

P.S. I managed to go back in and edit the text to correspond to the photos and then add the post script to this post. I'm obviously still in the learning process!!

P.S. I managed to go back in and edit the text to correspond to the photos and then add the post script to this post. I'm obviously still in the learning process!!

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2013

- Messages

- 3,898

Great video but the technique is a little bit hard on the object being tested, however, it would work well for determining the make-up of a supply of scrap was that you were about to re-purpose.

Getting back to the material used in making my Underhill/Simmons axe, I've been studying all the info and expertise that has been shared in this thread and found it rather fascinating. I didn't realize that there were so many possibilities for what materials and combinations could go into the making of an edge tool.

I also appreciate the fact that only I have had the privilege of examining the specimen in question with the naked eye; everyone else has had to rely on my mediocre photographic efforts. I wish you could all sit down with me, have a beer (I'm buying!) and pass this axe around for a closer examination. I think you might find that some of the conclusions that have been drawn have been the result of bad lighting or angles in my photos.

Upon my reexamination of the blade, I can't see any distinct demarcation indicating the use of two different kinds of steel or iron in its make-up. The third photo certainly appears to present the appearance that a cap was welded onto the poll. I'm afraid, however, that my cleaning process has falsely lead to that conclusion. Parallel to the flat surface of the poll, there was a bit of a concavity, perhaps due to some slight mushrooming, and, when I cleaned it, I had to aggressively rub with 150 grit sand paper through that trough. I think that lead to the appearance of two different metals being joined when that might not be the case.

I spent the last day or two examining blades (food choppers) that I'm sure have blades of one material welded to frames of another. Please check these photos:

,

,

The second photo is of a Swedish chopper with obvious forge welds joining a blade of one material to a frame of another. The two metals have very different colors and surface qualities. The first and third are of a no-name that appears to have a bit sandwiched into a frame of a different material. The photo of the edge shows at the arrow a forge weld that is much more obvious to the naked eye.

Now I'm no expert, and I might be missing something that more experienced eyes might see when examining my axe, but I can't convince myself that there is more than one type of metal there. Maybe I just don't know what to look for??

Again, I can't say enough how much I appreciate the time, effort and expertise you have all put into this discussion. Thank you much.

Are we still talking the same axe or build in general?

the-accumulator

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 906

I'm sure that there have been many axes built over the decades that have various types of Steel and or iron welded together, giving the axe a hardened edge and a softer frame. I'm just not convinced that my Underhill Simmons axe is made of more than one type of steel. The makeup of my axe came into the conversation in an attempt to help date the piece. If my axe is made entirely of a homogeneous steel, then I'm guessing it's no earlier than 1870 ish.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 28, 2010

- Messages

- 5,431

This catalog, said to be from 1873, has "Cast Steel Broad Axes" (whatever that means exactly) from D. Simmons & Co.

It looks like the broad axe in question is their "New York" pattern.

https://archive.org/details/DSimmonsAndCo1873/page/n1

It looks like the broad axe in question is their "New York" pattern.

https://archive.org/details/DSimmonsAndCo1873/page/n1

- Joined

- Aug 28, 2010

- Messages

- 5,431

From 1872, this article in Scientific American describes the axe-making process at "one of the largest ax manufactories in the country", that of Weed & Becker Co. (which took over after D. Simmons died in 1861). The axes are said to be made from iron and steel, with the iron bodies being cast in a mold, and then removed from the flasks, before the steel edges are added. About 150 dozen (=1800) axes and other tools are produced there on a daily basis.

...

Scientific American, Volumes 26-27, Sept 7, 1872, page 144

...

Scientific American, Volumes 26-27, Sept 7, 1872, page 144

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 28, 2010

- Messages

- 5,431

Interesting that the D. Simmons & Co brand of broad axes are still shown in this June 1905 list of prices for hardware stores:

Hardware, Vol. 31, June 10, 1905, page 95

Hardware, Vol. 31, June 10, 1905, page 95

Square_peg

Gold Member

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2012

- Messages

- 13,832

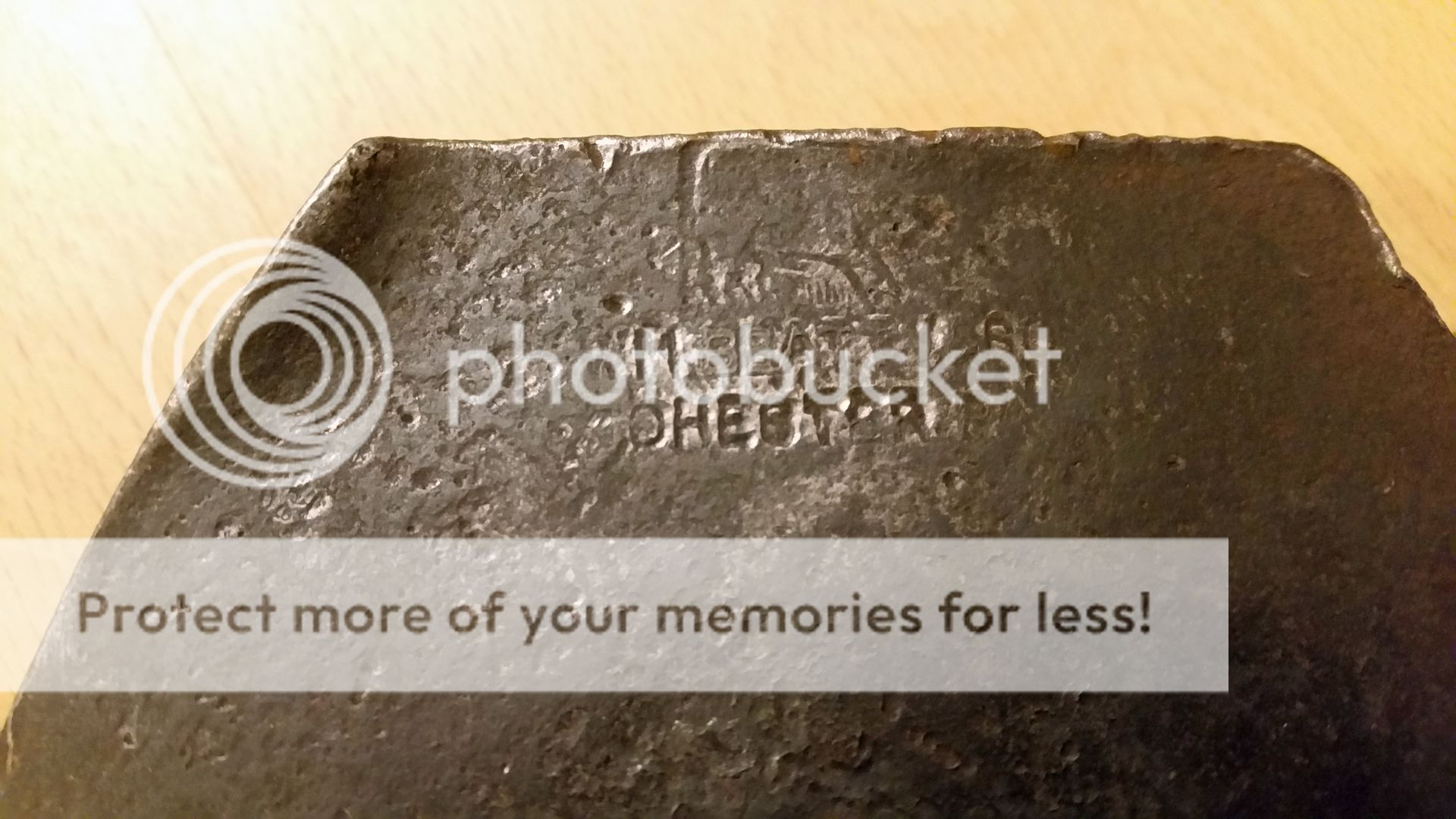

I did read the trove of information presented in this thread but I am wondering if the "Cohoes, NY" would help determine a range of years. I guess, meaning was there somewhat of a gauged period in which the plant in Cohoes operated and the Simmons axes where marked with it.

It's important to remember that as alliances came and went the rights to common labels were passed along and used again as the inheriting company's marketing department saw fit.

Interesting that the D. Simmons & Co brand of broad axes are still shown in this June 1905 list of prices for hardware stores:

Hardware, Vol. 31, June 10, 1905, page 95

Case in point.

Steve,you're an incredible hand at research,thank you so very much for all your work.

I'll try to read these documents forthwith,as my bandwidth here allows,though it may take me a couple days.

But very briefly,and Very generally,a quick note to T-A,the topic author:

Sir,you're very wise to be interested in all these details of old construction methods,it's really interesting,and educational,and a token of respect for all those craftsmen,engineers,metallurgists of those days.One of the best ways to learn the the history in general...

Forge-welding,fire-welding,is technically speaking Diffusion welding.In contrast to electric weld it does not involve liquifying (and mixing) of metals,but bringing materials close together,where under conditions of heat,pressure and freedom of contaminants the two parts begin to swap electrons,"knitting" themselves into one crystalline lattice(imperfectly,alas;in testing a forge-weld will Always part at the weld boundary).

In practice,a good sound forge-weld may be difficult to see.In the instance of edging of tools what sometimes gives it away is the Carbon content difference:the more C the Darker the metal will Etch.Emphasis on the Etch because in a clean,polished composite the difference may not be visible.

(air,moisture,oil from our hands et c. may act as etchants,being somewhat acidic,given time especially).

Also there may or may not be present some metallurgical effects like decarburisation(a hair-thin silvery trace),or gradual diffusion of C from higher to lower C content,and others.But again,there may be nothing at all,unless purposefully etched with serious acid,Nitric,Sulphuric,et c.

An axe from an established,reputable manufacturer would of course be Ground all over,the external traces of the weld obliterated.Seam is down to the bare metal.

Those Swedish choppers show the welds as they look like fresh from the forge-unground.The visible/palpable joint is the thin edge that became oxidised,contaminated with oxide during welding,and so cannot join the other side.

Sometimes,if it's practicable,the smith may work at Blending in the weld,making it invisible.It takes special effort,and must be justified.

Your photo of a blade with an arrow pointing at a dark-looking fracture may not be a (deliberate)weld at all.

Wrought Iron mentioned earlier(and according to Steve's data possibly not a part of this equation,i.e. the broadaxe discussed,so just for the record),is in itself a collection of welds:It was made by folding the material back on itself and welding it,again and again,forming many welded layers(those are what Ron in the video is demonstrating Delaminating).

So that fissure May just be a flaw one of the metal components,or a contaminated part of the blade material,with inclusions interfering between.

But getting back to the photos of the poll of your broadaxe.The fracture there speaks of the material being hardened.

So even if the visible(in photos)darker line is an illusion,that fracture indicates,albeit indirectly,the difference between two dissimilar alloys.

Otherwise the entire axe would have to be of sufficiently high C content for heat-treating,which is doubtful.(higher-C alloys are much stiffer,and in other ways more of a nuisance in forging,moreover unjustifiably more costly,for those times especially).

I'll try to read these documents forthwith,as my bandwidth here allows,though it may take me a couple days.

But very briefly,and Very generally,a quick note to T-A,the topic author:

Sir,you're very wise to be interested in all these details of old construction methods,it's really interesting,and educational,and a token of respect for all those craftsmen,engineers,metallurgists of those days.One of the best ways to learn the the history in general...

Forge-welding,fire-welding,is technically speaking Diffusion welding.In contrast to electric weld it does not involve liquifying (and mixing) of metals,but bringing materials close together,where under conditions of heat,pressure and freedom of contaminants the two parts begin to swap electrons,"knitting" themselves into one crystalline lattice(imperfectly,alas;in testing a forge-weld will Always part at the weld boundary).

In practice,a good sound forge-weld may be difficult to see.In the instance of edging of tools what sometimes gives it away is the Carbon content difference:the more C the Darker the metal will Etch.Emphasis on the Etch because in a clean,polished composite the difference may not be visible.

(air,moisture,oil from our hands et c. may act as etchants,being somewhat acidic,given time especially).

Also there may or may not be present some metallurgical effects like decarburisation(a hair-thin silvery trace),or gradual diffusion of C from higher to lower C content,and others.But again,there may be nothing at all,unless purposefully etched with serious acid,Nitric,Sulphuric,et c.

An axe from an established,reputable manufacturer would of course be Ground all over,the external traces of the weld obliterated.Seam is down to the bare metal.

Those Swedish choppers show the welds as they look like fresh from the forge-unground.The visible/palpable joint is the thin edge that became oxidised,contaminated with oxide during welding,and so cannot join the other side.

Sometimes,if it's practicable,the smith may work at Blending in the weld,making it invisible.It takes special effort,and must be justified.

Your photo of a blade with an arrow pointing at a dark-looking fracture may not be a (deliberate)weld at all.

Wrought Iron mentioned earlier(and according to Steve's data possibly not a part of this equation,i.e. the broadaxe discussed,so just for the record),is in itself a collection of welds:It was made by folding the material back on itself and welding it,again and again,forming many welded layers(those are what Ron in the video is demonstrating Delaminating).

So that fissure May just be a flaw one of the metal components,or a contaminated part of the blade material,with inclusions interfering between.

But getting back to the photos of the poll of your broadaxe.The fracture there speaks of the material being hardened.

So even if the visible(in photos)darker line is an illusion,that fracture indicates,albeit indirectly,the difference between two dissimilar alloys.

Otherwise the entire axe would have to be of sufficiently high C content for heat-treating,which is doubtful.(higher-C alloys are much stiffer,and in other ways more of a nuisance in forging,moreover unjustifiably more costly,for those times especially).

- Joined

- Aug 28, 2010

- Messages

- 5,431

A catalog from 1897 describes some pitfalls of using solid tool steel for axes (specifically "hatchets and hand axes"), and says "the present method" uses mild steel for the body and tool steel for the bit and poll. However, the downside of "the present method" is that tool steel and mild steel "do not take kindly to welding". So the catalog only has axes from William Beatty & Son, which still makes them "the old fashioned way", with tool steel bit and poll, and the body made from the "best Norway iron" (said to cost 2 or 3 times more than the mild steel alternative).

"Since the beginning of the present Steel Era or the Age of Steel, as it is commonly known, a great many tool manufacturers have brought out lines of solid steel Hatchets and Hand Axes. Solid Steel sounds very fine and is apt to lead a purchaser to expect that he is getting something extra good, but in our humble judgment this is a mistake. In the earlier experiments, the attempt was made to manufacture these tools of solid tool steel. This was found impracticable, as for some reason or other, tools made in this way were weak in the center or eye portion, and so it was we believe discarded. The present method is to use soft or mild steel for the center and tool steel for the cutting edge and head. Tool steel and soft steel haven t much of an affinity for each other and do not take kindly to welding. The Beatty tools are made in the old fashioned way. The body and eye being made of best Norway iron, with tool steel head and edge. This manner of making costs more, as the Norway iron is two or three times as expensive as common soft steel."

Wood Workers' Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery, and Similar Goods ...

Chas. A. Strelinger & Company, 1897

"Since the beginning of the present Steel Era or the Age of Steel, as it is commonly known, a great many tool manufacturers have brought out lines of solid steel Hatchets and Hand Axes. Solid Steel sounds very fine and is apt to lead a purchaser to expect that he is getting something extra good, but in our humble judgment this is a mistake. In the earlier experiments, the attempt was made to manufacture these tools of solid tool steel. This was found impracticable, as for some reason or other, tools made in this way were weak in the center or eye portion, and so it was we believe discarded. The present method is to use soft or mild steel for the center and tool steel for the cutting edge and head. Tool steel and soft steel haven t much of an affinity for each other and do not take kindly to welding. The Beatty tools are made in the old fashioned way. The body and eye being made of best Norway iron, with tool steel head and edge. This manner of making costs more, as the Norway iron is two or three times as expensive as common soft steel."

Wood Workers' Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery, and Similar Goods ...

Chas. A. Strelinger & Company, 1897

Square_peg

Gold Member

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2012

- Messages

- 13,832

Very enlightening, Steve!

the-accumulator

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 906

I am overwhelmed by the response I have gotten to my posts. I can't say enough how much I appreciate all the input that I have received. And, yes, I have learned/am learning, and, I hope, will learn much more about axes, metallurgy, forging, forge-welding, etc. as time goes by.

I, naturally, wanted my axe to be very old, very unusual, very finely made, and easy to accurately date. Of course I can,t make any of those things come true by wishing. And, regarding the markings, while they help in dating a piece and identifying the maker(s), we must first, as Mr. Levine says "Read the knife (axe)!"

"Reading" this axe has lead me to certain conclusions and mislead me to others. I have learned that very talented craftsmen combined various types of dissimilar metals so skillfully that, without acid etching, the welds can be invisible to the naked eye. Regarding my axe, I like what that implies: that my axe was very well made. At the same time, I'm a little disappointed that my axe wasn't made in the first half of the 19th century knowing that, if it was that early, it would probably display the more easily detected combination of iron and steel. But, as we know about any of our treasures, it is what it is!

Regarding the marks on my axe, while they should only be interpreted along with the piece itself, they certainly do shed some light about its history. While we know that J.Underhill and D.Simmons were applying their names to finely made edged tools as early as about 1831, we also know that at least some of these marks were used after 1900. I'm still hoping that further research will shed some light on a relationship between the two men, or, at least, a relationship that connects the two marks.

I love my Underhill/Simmons axe for what it is and have enjoyed owning it, cleaning it, and learning about it in this forum. I will now look at all my other axes, adzes, and hatchets, as well as many of my other old cutlery pieces (I am interested in and accumulate virtually anything with a sharp edge.) through different, more informed, eyes. Thanks again to all of you who have shared you time, your "likes", your experience, your research, and your passion with me.

I, naturally, wanted my axe to be very old, very unusual, very finely made, and easy to accurately date. Of course I can,t make any of those things come true by wishing. And, regarding the markings, while they help in dating a piece and identifying the maker(s), we must first, as Mr. Levine says "Read the knife (axe)!"

"Reading" this axe has lead me to certain conclusions and mislead me to others. I have learned that very talented craftsmen combined various types of dissimilar metals so skillfully that, without acid etching, the welds can be invisible to the naked eye. Regarding my axe, I like what that implies: that my axe was very well made. At the same time, I'm a little disappointed that my axe wasn't made in the first half of the 19th century knowing that, if it was that early, it would probably display the more easily detected combination of iron and steel. But, as we know about any of our treasures, it is what it is!

Regarding the marks on my axe, while they should only be interpreted along with the piece itself, they certainly do shed some light about its history. While we know that J.Underhill and D.Simmons were applying their names to finely made edged tools as early as about 1831, we also know that at least some of these marks were used after 1900. I'm still hoping that further research will shed some light on a relationship between the two men, or, at least, a relationship that connects the two marks.

I love my Underhill/Simmons axe for what it is and have enjoyed owning it, cleaning it, and learning about it in this forum. I will now look at all my other axes, adzes, and hatchets, as well as many of my other old cutlery pieces (I am interested in and accumulate virtually anything with a sharp edge.) through different, more informed, eyes. Thanks again to all of you who have shared you time, your "likes", your experience, your research, and your passion with me.

the-accumulator

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 906

Steve, thanks for the article about the "Beatty" method. I have a Beatty broad axe at home that now needs closer inspection! I'll let you know what I find. T-A

Yes,"Norway" iron was good stuff...Swedish,too,any Scandinavian products...With very high-quality ores,and theier systematic approach to things...(42 has posted some very interesting historical documents on this subject,wish that i was organised enough to keep track..

England,a major importer/exporter of steel of that day,was already down to using mineral coal.Whereby up north in Scandinavia with their endless coniferous forests charcoal was still used...Thus the best initial iron for crucible and other methods of steel manufacture was obtained from Norway and Sweden...(for in the Puddling process,an open-hearth way of burning excess Carbon from cast-iron(whehereby WI was obtained),mineral coal tends to contaminate the product with extremely unhandy Sulphur and Phosphorous,the both separately and together bane of ferrous metallurgy...).

That all stands to reason.

(And the Beatty description of the "disaffinity" is cute,i love it! ...I know from personal experience how when a weld refuses to stick one's mind turns to Poetry,and Myth...

...I know from personal experience how when a weld refuses to stick one's mind turns to Poetry,and Myth... ...a most traditional recourse,legends and songs have been composed on the subject throughout history!

...a most traditional recourse,legends and songs have been composed on the subject throughout history!

What blows my mind is the Casting part of the Weed & Becker process...I want to think it a typo,but no,with all the editing of that esteemed publication,and the exact technical descriptions following,it has to be right...

Just hard to wrap my pea-brain around that(sorry for these pointless musings,it has no bearing on this discussion).

Was it worth to have a separate Foundry part of an operation?Did they sub-contract it to one?

Just physically was it practical to pack a sand-casting flask,to cast what could be so easily just chopped off a rolled stock?

(their source must've not been that,but again,then it'd be a for real foundry set up,from ore...or some pre-processed product...)

Well,as much as it puzzles me,it obviously made practical/technical sense.

But in the metallurgical view their products must've been Something:Bringing iron to liquidus forces it to re-crystallise when cooling.

That structure then remains,reshaped and distorted by forging,but essentially intact.All future phase ransformations will take place along and in accordance with this internal structure.

It's important for highly critical applications such as gears,and such...But to have that structure inside one's axe!!!Incredible...I'd love to see some metallography from inside of one of those!

(again,sorry for digression)

England,a major importer/exporter of steel of that day,was already down to using mineral coal.Whereby up north in Scandinavia with their endless coniferous forests charcoal was still used...Thus the best initial iron for crucible and other methods of steel manufacture was obtained from Norway and Sweden...(for in the Puddling process,an open-hearth way of burning excess Carbon from cast-iron(whehereby WI was obtained),mineral coal tends to contaminate the product with extremely unhandy Sulphur and Phosphorous,the both separately and together bane of ferrous metallurgy...).

That all stands to reason.

(And the Beatty description of the "disaffinity" is cute,i love it!

What blows my mind is the Casting part of the Weed & Becker process...I want to think it a typo,but no,with all the editing of that esteemed publication,and the exact technical descriptions following,it has to be right...

Just hard to wrap my pea-brain around that(sorry for these pointless musings,it has no bearing on this discussion).

Was it worth to have a separate Foundry part of an operation?Did they sub-contract it to one?

Just physically was it practical to pack a sand-casting flask,to cast what could be so easily just chopped off a rolled stock?

(their source must've not been that,but again,then it'd be a for real foundry set up,from ore...or some pre-processed product...)

Well,as much as it puzzles me,it obviously made practical/technical sense.

But in the metallurgical view their products must've been Something:Bringing iron to liquidus forces it to re-crystallise when cooling.

That structure then remains,reshaped and distorted by forging,but essentially intact.All future phase ransformations will take place along and in accordance with this internal structure.

It's important for highly critical applications such as gears,and such...But to have that structure inside one's axe!!!Incredible...I'd love to see some metallography from inside of one of those!

(again,sorry for digression)

the-accumulator

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 906

A catalog from 1897 describes some pitfalls of using solid tool steel for axes (specifically "hatchets and hand axes"), and says "the present method" uses mild steel for the body and tool steel for the bit and poll. However, the downside of "the present method" is that tool steel and mild steel "do not take kindly to welding". So the catalog only has axes from William Beatty & Son, which still makes them "the old fashioned way", with tool steel bit and poll, and the body made from the "best Norway iron" (said to cost 2 or 3 times more than the mild steel alternative).

Here's my Beatty & Sons Chester PA broad axe (Pennsylvania pattern??) that clearly shows the combination of two different metals in its construction. It's a little worse for wear. It also has an applied finish on it that was compromised when I acquired it. In the course of cleaning it, however, I have found it very difficult to remove, even with aggressive scrapers and abrasives. I have no clue if it is a factory-original finish or was applied at a later date. Would Beatty have added a black or charcoal coating to a broad axe, or was that someone else's idea of an improvement?

,

,

I selected areas of bare metal (where the applied finish has been removed) where the two dissimilar metals meet and identified them with arrows. First the front:

Then the back:

While the border between the steel bit and the iron frame is quite obvious, I can't see evidence of a welded-on steel poll, although I suspect it's there. How ironic that Steve should come up with this Beatty info, and I should happen to have the perfect specimen to show as an example. Thanks, Steve, for all your research. T-A

While the border between the steel bit and the iron frame is quite obvious, I can't see evidence of a welded-on steel poll

T-A,the extra,added-on steeled poll on that broadaxe may very well Not be there...(afterall,it'd be quite unlikely that such a large,heavy tool of a strictly hewing nature be used to bump anything with it's poll...even wedges et c.).

But,yes,the weld-seams may be very difficult to discover and see.

It's just great,for our general education in axe-related issues,to be aware of the Possibilities of there being possibly a fairly complex composite structure.

For a historical note here's a picture of some of the possible combinations(it's of course way older than te 19th-20th c.c. American manufacture principles,but just for general awareness):https://imgur.com/a/ZUcTxks

(in a commonly accepted manner that schematic is shaded according to the Carbon content;the darker-the more C(as it pretty much is in real life,except when it's not

Also as an example here's a link to a working blog by one of the absolute best axe-smiths of our times,the inimitable Jim Austin:http://forgedaxes.com/blog/

In the photos of the top posting you'll see a quite uncommon shape of a steel insert.Not the most usual method,but it does illuminate the range of possibilities.

And lastly a technical note:As been said above the Diffusion weld does not create a monolithic structure,it always remains a weak point.

Thereby,it is always planned to be positioned so it'd act in Shear, to oppose the dynamic forces that'll be called for in the projected use of the tool.

the-accumulator

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 906

This catalog, said to be from 1873, has "Cast Steel Broad Axes" (whatever that means exactly) from D. Simmons & Co.

It looks like the broad axe in question is their "New York" pattern.

https://archive.org/details/DSimmonsAndCo1873/page/n1

Sorry, but please indulge me; I had to put this grouping together for a picture:

Broad axes: NEW YORK, WESTERN, PENNSYLVANIA, SHIP. Adzes: HALF HEAD, COOPERS', SHIP

I wish they were all in excellent condition, but they still make me smile when I compare them to the catalog image. T-A