- Joined

- Mar 4, 2018

- Messages

- 65

The folding knife is so rooted to the Spanish culture that no so long ago it was an habit to carry it by the poor, the rich, the man from the field and from the city. The youngest and oldest had their own folding knife that were displayed with pride.

This devotion was so fervent that among the people from Spain that, as Rafael Martinez del Porton describes on his book “The folding knives: study and collection”, in some regions such as Cartagena there was the tradition of “tomar la faca” (taking the blade). This ceremony was the ritual of passage from a boy to a man.

This ceremony was rooted to the mining people from this zone; when the “majo” (majo is an old term for describing a young boy, on the most cases under-age.) reached the 18 years old he took the blade, something like being name a knight. The majo wasn’t independent until that moment, and he should stay away from drinking wine or having a girlfriend.

This ceremony, as almost every popular celebration, was a party on the town, were relatives, majos and girls drank and danced. The dance was interrumpted so the majo could solemnly took the face from his father’s hands. The father made a cross in the air and said, “My son, I give you this face. This face courted your mother. It has not killed anyone, but it made me being respected. May God want you to be a man, as your grandparents did and your father did.¹

Sadly, something so beautiful, a tool used for generations, acquire a really bad reputation. A shady and traitor weapon, the tool of the unscrupulous and the wicked, this people give the folding knife a bad reputation.

In this way we can find the words of the Duke of Tobar, who affirmed in his book “Viajeros románticos por España” (“Romatic travelers through Spain”) that it is typical to engrave on the sword “Do not draw me without reason, and do not sheathe me without honor” but this words cannot fit on a folding knife, because it was a plebeian and populace weapon.

However, this completely distorts the importance of the folding knife, a tool that serves on the fields, trips, hunting, knife and cork on one tool, a blade that cuts and serves.

It cuts equally bread, meat and fish, and it can be even used as a spoon, with a piece of bread punctured on the tip and a bit of skill to drain every last drop of a stew.

We cannot forget on this point his use as a defensive weapon and in some cases, an honor keeper; we are talking about the folding knives duels. On this point, we will focus on Andalusia, the land where it comes the Sevilian folding knife, a land forged with sweet, fire and steel.

In that way, contradicting the Duke of Tobar, the fascination of these people for the folding knife reaches no limit. You can find any kind of engravings on these ancients folding knives such as:

“Do not unfold me without a reason and do not fold me without honor”

“The man propose and God dispose”

“If this viper bites you there is no remedy on the apothecary”

This kind of illustration shows the respect and the fascination the people of Andalucia have, they are tools but with a lot of temper.

As Teófilo Gautier pointed out on his book “Travelling through Spain”, the master of the dueling with folding knives are so many in Spain than the duelist masters in Paris.

Every folding knife “swordsman” has his own secret cuts and blows and they can recognized as the artist of a blow just seeing the wound, in the same way that you can identify a painter by some of their brushstrokes.

The ways of the Spanish folding knives are linked to Andalucia, with figures such as the “baratero”, people not exclusive from Andalucia but so abundant in this region.

On this matter, we find cities such as Seville or Almería, with winding streets, narrow and steep. These cities were the then of the worst of the worst, people of hard life, thugs, thieves and hullers. These people used to call their folding knives with knives such as: mojosas, chairas, teas, cortes, herramientas, hierros and abanicos.

The folding knives and their fencing is an ancient art of uncertain origin, however born or not in Andalusia, this lost knowledge will not be the same without the Andalusian folding knives. Masters in the fencing taught the bravest their rules, deadly blows, and how to avoid it. Dangerous people populate these lands, where you can figures such as the charrán and the baratero.

The charrán is no more than a slacker, a pariah that has made the art of doing nothing in his way of living. If he lives long enough on this life to get older, he will become a baratero, if a folding knife do not end up with such a tragic life.

Le Charran – Gustavo Doré – a: L’Espagne / par Le Baron CH. Davillier ;

The baratero was not exclusive from Andalusia, but here is where you could find such a refined ruffian. Men with an enviable mastery of the folding knife, an ability to steal and scamming never seen before. Feared by the players of illegals games.

Bad luck of the travelers who finds him in a dark alley, or poor devil who has the bad luck to start a fight with these barateros.

Barateros, with their Sevillian and Cordoban folding knives in hand dueled throughout the city, people from the suburbs that had some unwritten rules, the rules of honor amongst thieves. An honor that is maintained with steel, mastery and sometimes a bit of luck. (It is easy to be wounded by your own folding knife since it comes with no guard, so in the moment it got stuck by a bone your hand would slip across your own blade)

Some folding knives were perfected and crafted like the way of the knives from Arkansas or the Bowie, to remove the guts of a man or penetrate him from one part to the other if necessary.

Some folding knives were perfected and crafted like the way of the knives from Arkansas or the Bowie, to remove the guts of a man or penetrate him from one part to the other if necessary.

In order to conclude with this post, since an image worth more than a thousand words, I leave you here some images of my Andalusian folding knives.

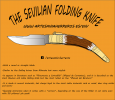

In this case, I am portraying a Sevillian folding knife compared with a Cordoban one. As you can see, the Sevillian folding knives resembles the ones from Albacete but more stylized, meanwhile the Cordoban has a straight shape that ends in oval or curved shaped.

I hope you liked this post! Unitl next writing!

This devotion was so fervent that among the people from Spain that, as Rafael Martinez del Porton describes on his book “The folding knives: study and collection”, in some regions such as Cartagena there was the tradition of “tomar la faca” (taking the blade). This ceremony was the ritual of passage from a boy to a man.

This ceremony was rooted to the mining people from this zone; when the “majo” (majo is an old term for describing a young boy, on the most cases under-age.) reached the 18 years old he took the blade, something like being name a knight. The majo wasn’t independent until that moment, and he should stay away from drinking wine or having a girlfriend.

This ceremony, as almost every popular celebration, was a party on the town, were relatives, majos and girls drank and danced. The dance was interrumpted so the majo could solemnly took the face from his father’s hands. The father made a cross in the air and said, “My son, I give you this face. This face courted your mother. It has not killed anyone, but it made me being respected. May God want you to be a man, as your grandparents did and your father did.¹

Sadly, something so beautiful, a tool used for generations, acquire a really bad reputation. A shady and traitor weapon, the tool of the unscrupulous and the wicked, this people give the folding knife a bad reputation.

In this way we can find the words of the Duke of Tobar, who affirmed in his book “Viajeros románticos por España” (“Romatic travelers through Spain”) that it is typical to engrave on the sword “Do not draw me without reason, and do not sheathe me without honor” but this words cannot fit on a folding knife, because it was a plebeian and populace weapon.

However, this completely distorts the importance of the folding knife, a tool that serves on the fields, trips, hunting, knife and cork on one tool, a blade that cuts and serves.

It cuts equally bread, meat and fish, and it can be even used as a spoon, with a piece of bread punctured on the tip and a bit of skill to drain every last drop of a stew.

We cannot forget on this point his use as a defensive weapon and in some cases, an honor keeper; we are talking about the folding knives duels. On this point, we will focus on Andalusia, the land where it comes the Sevilian folding knife, a land forged with sweet, fire and steel.

In that way, contradicting the Duke of Tobar, the fascination of these people for the folding knife reaches no limit. You can find any kind of engravings on these ancients folding knives such as:

“Do not unfold me without a reason and do not fold me without honor”

“The man propose and God dispose”

“If this viper bites you there is no remedy on the apothecary”

This kind of illustration shows the respect and the fascination the people of Andalucia have, they are tools but with a lot of temper.

As Teófilo Gautier pointed out on his book “Travelling through Spain”, the master of the dueling with folding knives are so many in Spain than the duelist masters in Paris.

Every folding knife “swordsman” has his own secret cuts and blows and they can recognized as the artist of a blow just seeing the wound, in the same way that you can identify a painter by some of their brushstrokes.

The folding knives from Andalusia

Making an approach to the folding knives from Andalucia, we can find the Sevilian and Cordoban folding knives, curved folding knives, similar to the ones from Albacete but more stylish; the most noble and refined among the folding knives.

The ways of the Spanish folding knives are linked to Andalucia, with figures such as the “baratero”, people not exclusive from Andalucia but so abundant in this region.

On this matter, we find cities such as Seville or Almería, with winding streets, narrow and steep. These cities were the then of the worst of the worst, people of hard life, thugs, thieves and hullers. These people used to call their folding knives with knives such as: mojosas, chairas, teas, cortes, herramientas, hierros and abanicos.

The folding knives and their fencing is an ancient art of uncertain origin, however born or not in Andalusia, this lost knowledge will not be the same without the Andalusian folding knives. Masters in the fencing taught the bravest their rules, deadly blows, and how to avoid it. Dangerous people populate these lands, where you can figures such as the charrán and the baratero.

The charrán is no more than a slacker, a pariah that has made the art of doing nothing in his way of living. If he lives long enough on this life to get older, he will become a baratero, if a folding knife do not end up with such a tragic life.

Le Charran – Gustavo Doré – a: L’Espagne / par Le Baron CH. Davillier ;

Bad luck of the travelers who finds him in a dark alley, or poor devil who has the bad luck to start a fight with these barateros.

Barateros, with their Sevillian and Cordoban folding knives in hand dueled throughout the city, people from the suburbs that had some unwritten rules, the rules of honor amongst thieves. An honor that is maintained with steel, mastery and sometimes a bit of luck. (It is easy to be wounded by your own folding knife since it comes with no guard, so in the moment it got stuck by a bone your hand would slip across your own blade)

In order to conclude with this post, since an image worth more than a thousand words, I leave you here some images of my Andalusian folding knives.

In this case, I am portraying a Sevillian folding knife compared with a Cordoban one. As you can see, the Sevillian folding knives resembles the ones from Albacete but more stylized, meanwhile the Cordoban has a straight shape that ends in oval or curved shaped.

I hope you liked this post! Unitl next writing!

- Rafael Martinez del Porton – The knives: A study and collection – Higher Council for Scientific Research – 1980.

Last edited: