Added from:

http://www.knife-expert.com/liners.txt

THE LINERLOCK -- RIGHT FROM THE SOURCE

Michael Walker's invention and development of the LinerlockTM

by Bernard Levine (c)1997 - for Knives Illustrated

The "Linerlock" knife is now so familiar that it is easy to

forget that both the knife and the name are relatively recent

inventions. Michael Walker made the first modern Linerlock in

1980, and he registered the name Linerlock as a trademark in

1989. Since the mid 1980s, dozens of hand knifemakers and factory

knife manufacturers have made locking liner type knives inspired

by Walker's designs, although very few of them fully understand

either the advantages or the limitations of this mechanism. The

best way to understand the Linerlock is to look back at how

Walker developed it.

THE EARLY DAYS

Mike Walker began to make knives early in 1980. One of his

first customers was a collector and dealer in Red River, New

Mexico, named Don Buchanan. Mike made ten fixed blade knives for

Buchanan. Don asked Mike for sheaths to go with these knives.

Mike made those leather scabbards reluctantly, then announced

that he hated making sheaths. So Don said, "Make folders."

Mike did. He made slip joints. He made lockbacks like the

factory folding hunters then on the market. He made mid-locks

with mechanisms copied from antique folders. But he was not

satisfied with any of these. Walker envisioned an improved folder

that would do away with what he saw as the many limitations of

conventional lockbacks.

First, he would design a knife that the user could open and

close safely and easily with one hand, without having to change

one's grip, or rotate the knife in one's hand.

Second, his new knife would do away with the sharp "back

square" of the conventional pocketknife blade. When a

conventional blade is closed, its back corner sticks out, and can

snag the user's clothing. In some folders the back square is

enclosed by extended bolsters, but this can compromise the shape

of the handle. Mike envisioned changing the basic geometry of the

folder, in order to eliminate the problem entirely.

Third, and most subtle, his knife would be self-adjusting

for wear. Other innovative folders of this period, notably the

Paul knife by Paul Poehlmann (patented 1976), were very strong

and very sleek, but they required careful adjustment of set

screws to keep their blades from working loose.

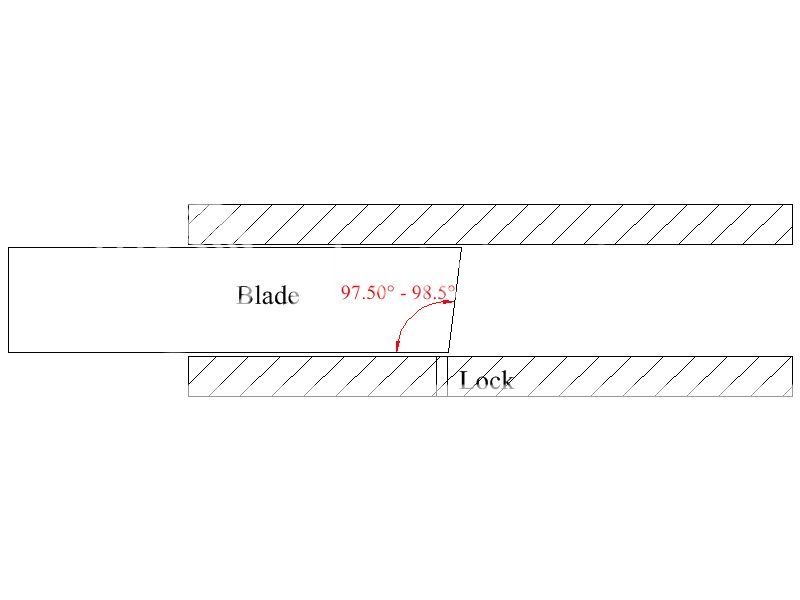

THE LOCKING LINER

Mike was familiar with the old locking liner design patented

by Watson & Chadwick in 1906 for Cattaraugus. Used first on

traditional folding hunters, this mechanism became standard on

electricians' pocketknives, and was also used on Cub Scout

knives. In this design, the liner projects above the handle, and

it is split lengthwise, alongside the pivot pin. The side of its

narrow tip engages the front edge of the tang when the locked

blade is open.

Mike noted that only a thin extension of the liner could be

used as the lock in the Watson & Chadwick design. This was

because most of the liner had to engage the pivot pin, in order

to hold the knife together against the tension of the backspring.

The result is that this type of lock is inherently weak.

Mike went back to first principles. He realized that if

spring tension and lock-up could be provided by a liner alone, he

would be able to dispense with the backspring entirely. With the

back spring gone, he could then have the end of the liner cut-out

engage the bottom end of the tang, making for a much stronger and

more positive lock. Indeed it would be nearly as strong as the

old Marble's Safety folder (patented in 1902), while dispensing

with that knife's long, awkward, and fragile fold-up extension

guard (the folded guard serves as that knife's lock when the

blade is opened).

STRONG AND SECURE

As it worked out, Mike had not anticipated just how strong

his new lock would be. About 1984 I helped to run side-by-side

destruction tests of all the types of locking folders available

at that time. Each test involved securing the handle of the knife

without blocking the movement of its blade or spring; then

sliding a one-foot pipe over the open blade (which was oriented

edge downward), to serve as a lever-arm; and finally hanging

weights from the free end of the pipe until the lock failed.

Name-brand conventional factory lockbacks failed at between

5 and 7 foot pounds (except for one that failed with just the

weight of the pipe). A Paul button-lock knife proved to be more

than twice as strong as the best of the conventional lockbacks.

But a Walker Linerlock was nearly four times as strong as the