-

The BladeForums.com 2024 Traditional Knife is available! Price is $250 ea (shipped within CONUS).

Order here: https://www.bladeforums.com/help/2024-traditional/

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Lets use those axes for what they were ment for.

- Thread starter rplarson2004

- Start date

From what I gather, there was a lot more than temperature working against the Titanic.

Are you suggesting that if the water had been a little warmer, the ship would not have sunk - after hitting an iceburg?

If it didn't actually hit an iceburg, then the engineers and shipbuilders had/have a lot of 'splainin' to do! They didn't know that the steel, rivets etc. weren't up to it? Would they have fared better in the Mediterranean? Where were the inspectors?

Again, I would like to see some data on how 20 - 50 degrees F changes the strength/elasticity of steel, and what difference it makes in the real world - particularly with axes and frozen logs. I have chopped a lot of holes through the ice on lakes and rivers (sometimes a couple of feet thick) and never had a problem. I assure you that any attempts to warm those axes first would have been utterly useless after the first swing!

Are you suggesting that if the water had been a little warmer, the ship would not have sunk - after hitting an iceburg?

If it didn't actually hit an iceburg, then the engineers and shipbuilders had/have a lot of 'splainin' to do! They didn't know that the steel, rivets etc. weren't up to it? Would they have fared better in the Mediterranean? Where were the inspectors?

Again, I would like to see some data on how 20 - 50 degrees F changes the strength/elasticity of steel, and what difference it makes in the real world - particularly with axes and frozen logs. I have chopped a lot of holes through the ice on lakes and rivers (sometimes a couple of feet thick) and never had a problem. I assure you that any attempts to warm those axes first would have been utterly useless after the first swing!

Square_peg

Gold Member

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2012

- Messages

- 13,854

There are some axes out there that I don't think you could chip no matter what you did to them.

Good point. A lot of cheap home owner axes are so soft they'd just roll an edge and never chip.

http://www.enggjournals.com/ijet/docs/IJET14-06-05-230.pdfFrom what I gather, there was a lot more than temperature working against the Titanic.

Are you suggesting that if the water had been a little warmer, the ship would not have sunk - after hitting an iceburg?

If it didn't actually hit an iceburg, then the engineers and shipbuilders had/have a lot of 'splainin' to do! They didn't know that the steel, rivets etc. weren't up to it? Would they have fared better in the Mediterranean? Where were the inspectors?

Again, I would like to see some data on how 20 - 50 degrees F changes the strength/elasticity of steel, and what difference it makes in the real world - particularly with axes and frozen logs. I have chopped a lot of holes through the ice on lakes and rivers (sometimes a couple of feet thick) and never had a problem. I assure you that any attempts to warm those axes first would have been utterly useless after the first swing!

Square_peg

Gold Member

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2012

- Messages

- 13,854

The effect of temperature is well documented on steel.

Does the Titanic ring any bells?

Cold water, not freezing, is enough to cause a hull failure.

"A massive crack in the bulk carrier Lake Carling occurred because the grade-A steel in the vessel's side shell was susceptible to brittle fracture in cold water, the TSB said in its report on the accident.

A minor crack in the hull of Lake Carling as it was crossing the Gulf of St. Lawrence on March 19, 2002, became a 21.5-foot-long hull fracture because of brittleness in the steel exposed to temperatures near 32°, according to the TSB report. "

http://www.professionalmariner.com/...-with-brittle-grade-A-steel-TSB-report-warns/

Good point. A lot of cheap home owner axes are so soft they'd just roll an edge and never chip.

I read somewhere that "you will never break a poor axe but you will a good one". It's how I feel about it and I do like them a little on the hard side. I am well aware that there are no free rides though just trade offs.

- Joined

- Nov 7, 2016

- Messages

- 796

Cold water, not freezing, is enough to cause a hull failure.

"A massive crack in the bulk carrier Lake Carling occurred because the grade-A steel in the vessel's side shell was susceptible to brittle fracture in cold water, the TSB said in its report on the accident.

A minor crack in the hull of Lake Carling as it was crossing the Gulf of St. Lawrence on March 19, 2002, became a 21.5-foot-long hull fracture because of brittleness in the steel exposed to temperatures near 32°, according to the TSB report. "

http://www.professionalmariner.com/...-with-brittle-grade-A-steel-TSB-report-warns/

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&sou...XXatPtOr4xI7Nu1XQ&sig2=o8gOw_cdQSdxnKsIYXMpBA

- Joined

- Nov 7, 2016

- Messages

- 796

Well, for my money I'll take the experience and (most importantly) documentation of S_p's trail work and temps over the peanut gallery's internet knowledge and arts and crafts.

Sheesh.

Mmmm. Facts. What are the facts? That Square peg was "heating" up a bit with a bic lighter? On a day he claims was °25 degrees F. A day that the national weather service said was 40° in his state. Sure temps vary throughout a state. He has chipped a bit twice he has shown, both on the same type of wood. Both with admittedly thin bits. Mmmmm. In the second picture there is some suspicious wet green plant in the picture that tells me the temperature was not below freezing. Lol. The only constants are the type wood? And the admittedly thin bit. Did I get that about right? Mmmmmm. Internet knowledge? No. Just curious axe fans discussing the actual temperature that tempered steel of an axe bit becomes more brittle. As I understand it it is below freezing and then some before an axe bit becomes brittle. As in far closer to 0°F than 32°F.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Nov 7, 2016

- Messages

- 796

So you're accusing S_p of making up the temps he was working in? Ok. 87 posts, and about half of them are arguments. Mmmmm...on the ignore list you go, troll.

I am stating the temperature the national weather service said it was in his state. (I believe I even specifically searched maple valley and it said 40°f)While acknowledging temp vary throughout a state and area(and throughout the day) he has listed he is in. And making the observations about clothing worn and wet plants. As I said, I live and use axes in a place that gets cold. My experience is different than his. I believe he is misdiagnosing the cause of his chips. If you can not handle, or in your case understand what is written, that as it is it is on you.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Nov 7, 2016

- Messages

- 796

From what I gather, there was a lot more than temperature working against the Titanic.

Are you suggesting that if the water had been a little warmer, the ship would not have sunk - after hitting an iceburg?

If it didn't actually hit an iceburg, then the engineers and shipbuilders had/have a lot of 'splainin' to do! They didn't know that the steel, rivets etc. weren't up to it? Would they have fared better in the Mediterranean? Where were the inspectors?

Again, I would like to see some data on how 20 - 50 degrees F changes the strength/elasticity of steel, and what difference it makes in the real world - particularly with axes and frozen logs. I have chopped a lot of holes through the ice on lakes and rivers (sometimes a couple of feet thick) and never had a problem. I assure you that any attempts to warm those axes first would have been utterly useless after the first swing!

I think this is a case of someone misdiagnosing the cause of a problem and not understanding what extreem cold actually is.

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2013

- Messages

- 3,898

This thread was 25 pages deep until someone mentioned warming their axe bit up before work - I personally scanned right over that.

Now it's about the Titanic, who is older, who knows "real cold", and whether a Pulaski should have a handle the user likes? You are ruining a thread based on one comment in thousands.

As far as I can see, he essentially responded with "You do what you want with yours and I do what I want with mine". That should have been enough.

Since moving targets are more fun:

"Snazzy" ooh-la-la bedazzled girlie-man soft-handed warm-weather eye candy. Not even sharpened...

Mr. Chips - 1. your Christmas ornaments are super impressive, 2. we get it - You don't think it's necessary to warm the bit, and 3. your initial post is in effect rife with disdain that crosses into the personal.

Woodcraft Just work for the forces of Good, eh?

So Chips, next time you are chopping wood and someone tells you to warm the bit, just tell them no. After 60+ years in Kelvin measured weather you have earned at least that.

Whether or not warming the bit is necessary, he didn't invent it, you dont have to do it, and it certainly didnt hurt a thing.

And here is something else to keep in mind If I dropped in on one of your threads and saw something that you do in practice that in absolutely no way hurts your carving knives or is actually necessary, I would scan right over it to the substance of what you had to say.

All this without having to make negative comments.

By keeping at this you are maintaining this thread at the top of the page. By doing that you are drawing ALL attention to who is right on one SMALL detail.

My guess is that someone is going to step in and stifle this thread and if that happens? It won't be because Square_peg warmed his bit.

Now, someone post a picture of chopped wood - it's too cold outside for me. Brrrrrrrr.

Now it's about the Titanic, who is older, who knows "real cold", and whether a Pulaski should have a handle the user likes? You are ruining a thread based on one comment in thousands.

As far as I can see, he essentially responded with "You do what you want with yours and I do what I want with mine". That should have been enough.

Since moving targets are more fun:

"Snazzy" ooh-la-la bedazzled girlie-man soft-handed warm-weather eye candy. Not even sharpened...

Mr. Chips - 1. your Christmas ornaments are super impressive, 2. we get it - You don't think it's necessary to warm the bit, and 3. your initial post is in effect rife with disdain that crosses into the personal.

Woodcraft Just work for the forces of Good, eh?

So Chips, next time you are chopping wood and someone tells you to warm the bit, just tell them no. After 60+ years in Kelvin measured weather you have earned at least that.

Whether or not warming the bit is necessary, he didn't invent it, you dont have to do it, and it certainly didnt hurt a thing.

And here is something else to keep in mind If I dropped in on one of your threads and saw something that you do in practice that in absolutely no way hurts your carving knives or is actually necessary, I would scan right over it to the substance of what you had to say.

All this without having to make negative comments.

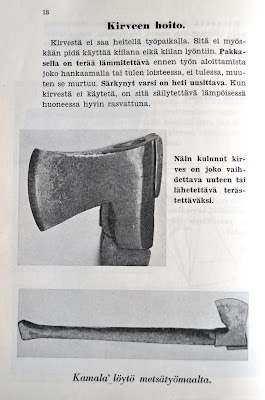

Those Finns seem to be my kind of people!

His scanned book page a little way down has some Finnish text on it that was interesting:

https://northernwildernesskills.blo...howComment=1481757867425#c4884596261083006500

"The axe is not to be thrown in the workplace. Nor is it to be used as a wedge or wedge shot. If temperature is below freezing the blade is heated up before starting work, either by rubbing or the glow of the fire, not the fire itself, or it will break. A broken arm (varsi - handle) is immediately replaced. When the axe is not used, it must be kept in a warm room well greased"

By keeping at this you are maintaining this thread at the top of the page. By doing that you are drawing ALL attention to who is right on one SMALL detail.

My guess is that someone is going to step in and stifle this thread and if that happens? It won't be because Square_peg warmed his bit.

Now, someone post a picture of chopped wood - it's too cold outside for me. Brrrrrrrr.

Last edited:

I was enjoying the extreme cold debate. My first reaction was that SqP was being a bit indulgent to his Pulask, which I think he admittedi, but that is his perogative, however, and I can't see it doing any harm. Plus, wood stays frozen for a while even after temps rise. I chopped some frozen red cedar at about 10-15 degrees and got tiny micro chips in the edge of my true temper. Overnight lows had been 0 to minus 5 or ten for several days, which is unusually low for here and I was thinking it was fairly extreme cold for most of my neighborhood  . No real harm to the axe (very hard and tough) and I didn't know about it until I start trying to figure out why it was having a hard time with what is normally an easy task.

. No real harm to the axe (very hard and tough) and I didn't know about it until I start trying to figure out why it was having a hard time with what is normally an easy task.

Long story short, I think there are merits on both sides and I'd like to see more data on temperature effects on steel, minus recriminations.

Just as a data point, I use a hatchet to clear ice from water buckets regularly and haven't noticed any problem even for cheap axes, but wood is different.

Long story short, I think there are merits on both sides and I'd like to see more data on temperature effects on steel, minus recriminations.

Just as a data point, I use a hatchet to clear ice from water buckets regularly and haven't noticed any problem even for cheap axes, but wood is different.

Does ice get colder than 32F/0C? If it does, is it harder then?

What about green wood? There is a lot of water in there.

I don't know the answers to the above questions, maybe someone out there does.

It might help us understand what chopping in cold temperatures does to the axe.

What about green wood? There is a lot of water in there.

I don't know the answers to the above questions, maybe someone out there does.

It might help us understand what chopping in cold temperatures does to the axe.

- Joined

- Nov 7, 2016

- Messages

- 796

While the bit of an axe is subject to stress from use that is different, or perhaps magnified and subject to be affected more by less, this paper leads me and experience lead me to believe that you have to be pushing 0°f to have the steel of an axe bit be affected in a major way.Does ice get colder than 32F/0C? If it does, is it harder then?

What about green wood? There is a lot of water in there.

I don't know the answers to the above questions, maybe someone out there does.

It might help us understand what chopping in cold temperatures does to the axe.

As far as "frozen" trees, the Michigan pattern claims its pattern of rounded corners as a direct response to chipping bits in frozen pine. I have no doubt that frozen knots are hell on a bit. There is a diagram, I believe from Kelly axe, that shows what chips are normal and what chips are from a defective temper.

Small dents and chips and dings are quite normal on an axe. And bigger chips, in my experience, are almost always a result of a thin edge. My point in joining in the conversation was not to just call out the person, but to point out the absolute lack of information supporting what temperature is cold enough to require heating up an axe.

In case people do not want to click on a link.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&sou...XXatPtOr4xI7Nu1XQ&sig2=o8gOw_cdQSdxnKsIYXMpBA

Quenched and tempered low-alloy steels are, of course, applicable at temperatures

down to -50°F, and many of them.are suitable for use at temperatures down to -lOO°F or

-150°F, but these will be discussed more fully in the next section.

Practically all aluminum and titanium alloys may be used in critically stressed

applications at temperatures down to -SOOF, except for some of the highest-strength

aluminum alloys such as 7178-T6 and 7075-T6. These are not recommended, especially

where sharp changes in section, complex stress distributions or impact loads are in-

volved. Similarly, the all-beta 13V-llCr-3Al-titanium alloy (12OVCA) and the 8 Mn-

titanium alloy tend to be notch-brittle at moderately reduced temperatures.

Nickel and copper-base alloys are virtually all suitable for use at temperatures

down to -50°F, and generally much lower.

Metals for use to -150'F. Low-alloy steels suitable for use at temperatures

down to -150°F fall into two categories: quenched and tempered steels having essen-

tially fine-grained, tempered, martensitic microstructures, and nickel-alloyedcfer-

ritic steels. Most of the lower carbon (0.20 to 0.35% C) low-alloy steels having

sufficient hardenability to achieve martensitic microstructures through the section

thickness when either water- or oil-quenched are, after tempering at appropriate tem-

peratures, sufficiently tough for most critical service applications at temperatures

down to at least -10O0F. Many of these steels contain several alloying elements such

as manganese, nickel,. chromium, molybdenum and vanadium. Several contain small quan-

tities of zirconium or boron, the latter having a potent effect on increasing harden-

ability. These steels include proprietary grades such as T-1 and N-A-XTRA, among

others, as well as standard grades such as 'AMs 6434, 4130, 4335, etc.

Although the above steels are usable to at least -lOO°F, they may, depending

upon steel-making practice, tempering temperature, etc., undergo the tough-to-brittle

transition at some temperature between -lOO°F and -150'F. For more reliable perform-

ance at the lower end of this temperature range, it is necessary to employ somewhat

more highly alloyed quenched and tempered steels such as HY-80 or HY-TUF, both of

which are proprietary steels.

Low-carbon 3yk nickel steel is widely used in large land-based storage tanks to

contain liquefied gases at temperatures down to -150'F. This steel falls under ASTM

A203, Grades D and E, and is subject to impact tests in accordance with. the require-

ments of A-300.

As shown in Fig: 7, a large number of aluminum, nickel, and titanium-base alloys

The high-strength 7079-T6 aluminum alloy may be used down to -200°F, but is

' are suitable for critically stressed applications at temperatures down to -150°F and

lower.

not recommended for lower-temperature applications. In the case of titanium alloys,

the 6A1-6V-2Sn-Ti alloy in the heat-treated condition may be used at temperatures

down to -40°F, and the 16V-2.5Al-Ti alloy may be used down to -lOO°F, but neither is

recommended for use at temperatures lower than these.

- 318 -

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I Metals' for use at -320'F. Increasing the nickel content of low-carbon steel

progressively reduces the temperature of transition from duetile to brittle fracture

as shown in Fig. 3a. In the normalized and tempered condition, a steel with 9% nickel

has a keyhole-notch Charpy impact energy of 30 ft-lb at -320'F. In the quenched and

tempered condition the same steel will show 50 ft-lb impact energy at this temperature.

ASTM A353-58 covers the 9% nickel grade and requires the normalized and tempered heat

treatmqnt. Revision of current pressure-vessel codes to permit quenched and tempered

steel of this grade for pressure vessels will result in improved reliability of low-

temperature storage tanks.

The austenitic stainless steels of the Type 300 series are all suitable for use

at -320°F, as is the heat-treatable A-286 stainless steel. Precipitation-hardenable

stainless steels of the PI3 series are not recommended for subzero temperature applica-

tions since they evidence notch embrittlement at temperatures between OoP and -4OOF.

The recently developed maraging steels of the 20% and 25% nickel varieties, with

various amounts of cobalt, molybdenum, titanium, aluminum and columbium added, exhibit

notch toughness at temperatures down to at least -320°F, and possibly down to liquid-

hydrogen temperature. The maraging steels are readily formable and weldable, and are

hardened by a relatively low-temperature aging at 900°F.

A large number of aluminum alloys, including 2024-T6, 7039-T6, 2014-T6, and

5456-H343 have excellent resistance to brittle fracture at -320°F, although weld joints

in the 20144'6 alloy tend to exhibit brittle behavior at low temperatures.

minum alloys of the 5000 series aluminum-magnesium type are also tough at -320°F and

at. lower temperatures, as are the 6061-T6 and 2219-T87 alloys.

Other alu-

Nickel-base alloys are almost all tough at -320°F, as shown in Fig. 7.

alloys such as the 6A1-4V-Ti (both in the annealed and heat-treated conditions), the

8Al-2Cb-1Ta-TiY and the 5Al-2.5Sn-Ti alloys are ductile and tough at -320°F. It has

been found that impurity elements such as oxygen, nitrogen and carbon, as well as' iron,

can embrittle these alloys at low temperatures; care should be taken to keep these im-

purities as low as possible in materials intended for critical applications at very

low temperatures.

Metals Gorp. of America led to the development of the ELI (extra low impurity) grades

of the 6A1-4V-Ti and 5A1-2.5Sn-Ti alloys.

There is a large gap between the temperature of

Titanium

Cooperative work at General Dynamics/Astronautics and Titanium

Metals for use below -320'F.

liquid nitrogen, -320°F, and that of the next lower-temperature liquefied gas of im-

portance, liquid hydrogen, which boils at -423OF. Liquid helium, boiling at -452'F,

is the only other cryogen that fills this low-temperature range. Liquid hydrogen,

because of the space program, has become of wide commercial significance, and a pro-

duction capacity in the tens of thousands of tons per year has been established here

within the past few years.

Among the steels, only the more highly alloyed austenitic stainless steels are

suitable for use at liquid-hydrogen or helium temperatures. Types 304 and 310 stain-

less steels fall within this classification, and the low-carbon grades of these steels

are recommended, especi.ally when welding is to be perfarmed. There are a number of

low-carbon stainless-steel casting alloys containing generally 18 to 21% chromium and

9 to 14% nickel that may be used for piping, valve bodies, flanges, etc., at -423OF

or lower.

The aluminum alloys that may be safely used at liquid-hydrogen temperatures in-

clude several of the 2000 and 5000 series, as well as the 6061-T6 alloy. Weldments

of the 2219-T87 alloy have demonstrated excellent resistance to brittle fracture at

-423OF, while the lower-strength 5052-H38 and 5083-1138 alloys have also showed good

notch-toughness at: this temperature

I

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jan 5, 2016

- Messages

- 127

It might help us understand what chopping in cold temperatures does to the axe.

Steel gets more brittle the colder it gets. Too brittle and it essentially behaves like a piece of glass -- hit it too hard and it cracks. A localized hard point like a knot produces a lot of force in a small area and overloads the strength of the steel in the region which causes chipping, much like a stone chip in your windshield.

I don't have any idea a what temperatures this becomes a concern, but it would vary due to composition of steel. I believe higher carbon content aggravates the issue but I'd have to dig out and dig through a couple of old welding books to confirm it.

- Joined

- Jan 8, 2012

- Messages

- 147

T2 Tappin'

Square_peg

Gold Member

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2012

- Messages

- 13,854

Wow! there are still leaves on the trees in N.C. Must be nice.

Looks like your tree fell in the right direction.

Looks like your tree fell in the right direction.