This is the problem of scale...

What is the problem you are having? I did not give a scale to the diagram/schematic provided. It could be on the order of microns or of inches, all that matters is that it is representative of the actual bevel AND the apex is sufficiently keen.

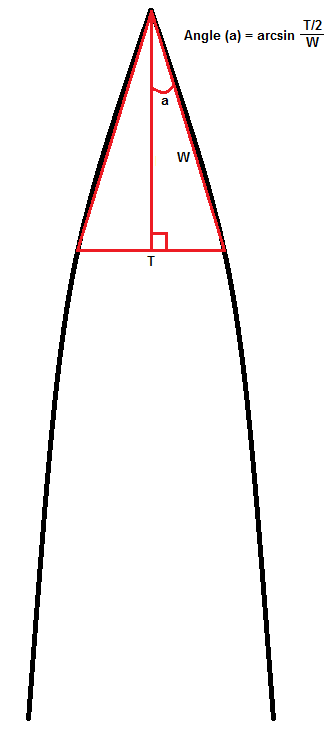

As I already defined it, the effective edge angle is the angle above which an edge will actually engage its target. Drawing a straight line within a convex to approximate the edge angle does not work at the macroscopic level. If you were to try approaching a flat piece of paper or wood at such a calculated angle the edge would almost certainly not engage because the actual effective angle would be greater due to the convexity.

Yes it does work, it works at

any scale while a tangent does

not work at any scale. From your description, the problem lies with

where your edge is most convex, i.e. what flat-angle best approximates the cutting performance (to pinnah, it is all about performance, the point of the schematics and micrographs is to dispel confusion about the reality of the performance achieved). What you have described - approaching a flat surface with your edge and not engaging - at what angle are you engaging the surface? You have used a wood-plane, yes? Even with a face-razor on pliable skin, you cannot engage the surface with the bevel flat, it must be elevated. The degree of elevation and the

thickness of the bevel (be it flat or convex) determines the depth to which it engages in a cut. Planing wood a common angle of engagement is ~50 degrees with a blade sharpened to >30 degrees inclusive, shaving it's commonly ~30 degrees for a blade sharpened to ~17 degrees inclusive, and most other cutting tasks use an even greater angle to engage. That is practical reality.

Note in the image that the blade has a wear-profile the forms a less acute microbevel as the cut proceeds.

Please note that this diagram was made from a planer on cherry wood (very hard) that continued to engage its target even at the fullest point of wear. Again, since you cannot measure the "tangent" of the convexity, how would you measure the effective edge angle?

Understand that even planing cherry-wood - much stiffer than paper or a pen which you might be using to pretend to test edge-angle - there is enough flexibility in the surface to allow for

some penetration (i.e. engagement) despite the progressive loss of clearance, and that convexity is rather dramatic, MUCH more dramatic than what i present in my schematic measuring effective edge angle. To measure the effective edge-angle of the worn planer, you would do as I did before, calculating the angle from the thickness and height of the worn part of the bevel. If you try doing it your way, i.e. checking for engagement at a specific angle, you are really just measuring clearance and flexibility of the material you are cutting and perhaps the keenness of the edge (i.e. diameter of apex), NOT edge angle "effective" or otherwise. Please note, i can shave/engage my facial hairs as well with a 40-degree edge as with a 10-degree edge so long as the edge is sufficiently keen, what is different is the amount of wedging that occurs

after the edge has engaged. In an earlier schematic i showed a thick SYKCO 511 and an RMD with the same

edge angle, but the SYKCO had less clearance due to the thickness of the bevel

behind that of the RMD, so on some material it would have more trouble planing off shavings because the bevel would be up against the material being cut if i laid the blade at a lower angle than the edge, but the RMD might be able to compress the material with the edge-shoulder enough to allow the edge to engage despite being at the same angle, and both were stropped to a convex edge-angle.